|

Employee Engagement and Internal Communication:

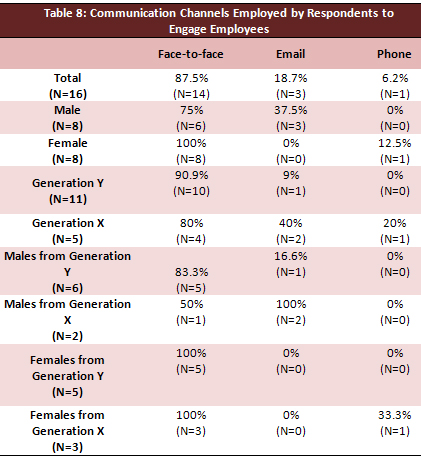

A United Arab Emirates Study

Kate

O'Neill

Sasha Hodgson

Mariam Al Mazrouei

Zayed

University

United Arab Emirates

Corresponding author:

Kate O'Neil

Zayed University

United Arab Emirates

Email:

Kate.ONeill@zu.ac.ae

1. Introduction

Chapter 1 of this research paper provides

an overview of the study, explains

the purpose of the study, presents

the methods of data collection and

analysis, states the areas reviewed

from existing literature, and describes

the remaining chapters of this research

paper.

Study Overview

The study explored which internal

communication channels contribute

to an employees' sense of engagement

and how these channels serve to promote

engagement in 16 Emirati employees

in a federal organization in the United

Arab Emirates. Findings indicated

the participants felt most engaged

at work when face-to-face communication

was used. When the participants wanted

to engage colleagues, they also employed

face-to-face communication channels.

Cultural influences were pivotal in

the participants' communication channel

selection.

Purpose of the Study. The purpose

of this exploratory study was to further

understanding of, and contribute to,

the scant research on the United Arab

Emirates (Bristol-Rhys, 2010) employee

engagement and internal communication

in the United Arab Emirates. The study

aimed to determine which internal

communication channels contribute

to an employees' sense of engagement

and how these channels do this.

Design, Methods, and Analysis.

Data were collected via a one-hour

interview with each participant over

a four-week period. Interviews were

conducted face-to-face. Open-ended

questions were administered in a semi-structured

format to acquire participants' point-of-views

and experiences.

The interview method was selected

because (a) it has been noted to be

ideal for qualitative research (Cachia

& Millward, 2011) and (b) it has

been successfully used with Emirati

participants (e.g., Al Jenaibi, 2010;

O'Neill, 2011).

Two interview questions achored this

study: (a) Which internal communication

channels contribute to engaged employees'

sense of engagement? and (b) How these

channels facilitate this.

Data were analyzed for thematic content.

The goal of the analysis was to identify

themes and patterns in the communication

channels selected by the participants

and the reasons for selecting these

channels.

Implications for Practice.

Findings from this study may be used

to promote Emirati employee engagement.

It may also be beneficial for expatriates

in leadership roles in Emirati organizations

as communication channels that engage

Emiratis may be completely different

than those that engage expatriates.

Document Overview. Chapter

2 examines concepts relevant to the

study in order to ground it academically.

Chapter 3 explains the data collection

methods used in this study. It also

describes the participant population

and the method of data analysis. At

the end of chapter 3, ethical considerations

are presented. The data is presented

in chapter 4. Chapter 5 presents interpretation

of the findings and limitations of

the study.?

2: Literature

Review

The purpose of this exploratory study

was to further understanding of, and

contribute to, the scant research

on employee engagement and internal

communication in the United Arab Emirates.

The study aimed to determine which

internal communication channels contribute

to employees' sense of engagement

and how these channels do this.

Employee Engagement

Employee engagement (EE) is a business

management concept that is gaining

popularity as only recently has employee

engagement been recognized as an essential

element of organizational success

(Gallup, 2012). Researchers have posited,

"Employee engagement is, arguably,

the most critical concern for organizations

in the 21st century" (Leadership

Insights, 2011, p. 7). This assertion

was supported by a 2012 Confederation

of British Industry (CBI) study showing

that 60% of employers planned to prioritize

employee engagement in the upcoming

year.

Over the years, employee engagement

has existed under different names

such as 'employee behavior', 'employee

satisfaction' and 'job satisfaction'

(Mumford, 1972).

Definition. Kevin Kruse, author

of Employee Engagement 2.0, defined

employee engagement (EE) as "the

emotional commitment the employee

has to the organization and its goals"

(Kruse, 2012, p. 1). According to

Towers Watson (2010), a leading international

professional services company, employee

engagement is the amount of "discretionary

effort" (p. 2) employees put

into their work. The Gallup Organization,

a research-based performance management

consulting company, has conducted

more than 30 years of research on

employee engagement and it defines

employee engagement as "the individual's

involvement and satisfaction with,

as well as enthusiasm for, work"

(Balain & Sparrow, 2009, p.8).

In 2010, Shuck and Wollard studied

140 articles published between 1990

and 2008 to determine consistencies

and differences in EE definitions.

Their research confirmed a 2006 Conference

Board report concluding that employee

engagement lacks a consistent definition.

This was underscored by Doherty (2010)

who asserted, "[E]mployee engagement

is one of those often talked about

but rarely understood concepts"

(p. 32).

However, researchers do concur that

"employee engagement is not just

about having enthusiastic, happy workers"

(Richman, 2006, p. 36); EE entails

"an emotional connection to the

organization, a passion for work and

feelings of hope about the future

within the organization" (Gross,

2007, p. 3). Other characteristics

of employee engagement that researchers

seem to agree on include: loyalty,

advocacy, trust, and job satisfaction

(Ames, 2012).

For the purpose of this study, employee

engagement is defined as "the

emotional commitment the employee

has to the organization and its goals"

(Kruse, 2012, p.1).

Importance of Employee Engagement.

Research indicates there is a

positive relationship between employee

engagement and organizational performance

(Aon Hewitt, 2012). Research also

suggests that engaged employees are

(a) more productive (Clampitt &

Downs, 1993), (b) innovative (Linke

& Zerfass, 2011) and (c) have

increased psychological wellbeing

(Robertson & Cooper, 2010) and

EE is linked to (a) employee retention,

(b) employee performance, and (c)

organizational profitability (Balain

& Sparrow, 2009; Hughes &

Rog, 2008; Macey & Schneider,

2008).

Furthermore, research has shown there

is a mutually beneficial relationship

between EE and organizational profitability

(Towers Watson, 2010). The Hay Group

noted, "[I]n good times engagement

is bolstered by high profits, in difficult

times, engagement drives up profits"

(2012, n.p.). A study conducted by

Gallup in 2012 on a large number of

international organizations and their

employees from various industries

established "that employee engagement

strongly relates to key organizational

outcomes in any economic climate"

(Gallup, 2012, n.p.). The effects

of employee engagement on outcomes

have been found to include:

• 25% lower turnover (in high-turnover

organizations)

• 65% lower turnover (in low-turnover

organizations)

• 48% fewer safety incidents

• 41% fewer quality incidents

(defects)

• 21% higher productivity

• 22% higher profitability

Drivers. A survey study(1)

by MSW Research and Dale Carnegie

Training involving 1,500 employees

in the United States explored the

key drivers of employee engagement.

The researchers concluded there are

three main drivers of employee engagement:

(a) "relationship with immediate

supervisor, (b) belief in leadership,

and (c) pride in working for the company"

(Dale Carnegie & Associates, 2012,

p. 2). Additional studies by Gallup

(2008, 2010, 2012) found the following

to be key drivers to employee engagement

• Encouragement from superiors

• Work-life balance

• Belief in the mission and vision

of the organization

• Praise and recognition

• Sense of concern for well-being

• Adequate pay and benefits

• Well-defined job expectations

• Resource sufficiency

• Opportunities to use skills

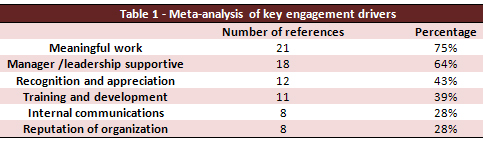

A 2013 analysis of 28 consultancy-conducted

research studies indicated the main

non-financial drivers of employee

engagement most frequently mentioned

included meaningful work, manager

support, and recognition and appreciation.

(Pascoe, 2013)

Although there may be areas of concordance,

researchers have stated there is "no

definitive all-purpose list of engagement

drivers" (CIPD, 2007, p. 2).

While pay and benefits motivate employees,

researchers state that they are not

effective employee engagement drivers

(Branham, 2005; Devi, 2009; Campbell

& Smith, 2010). Maslow (1954)

emphasized the importance of individuals

having a sense of belonging (i.e.,

engagement).

According to a study by the Kenexa

Research Institute (2012) that surveyed

employees in 40 countries, employees

are engaged in a similar manner. While

the ways of engagement may be different

to better suit cultural sensitivities,

an employee's needs and psychological

motivations remain constant (Hofstede

Centre, 2013).

History. A look into the history

of employee engagement reveals that

in the 1940s employee engagement was

associated with entertaining employees.

In the 1950s employee engagement was

correlated with informing employees,

which then became persuading employees

in the 1960s. EE shifted to employee

satisfaction in the 1970s and in the

1980s employee engagement was likened

to open communication and commitment.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the relationship

between employee engagement and effectiveness

emerged (HayGroup, 2012).

The employee-employer relationship

first emerged in 1911 when Frederick

Taylor published his theory of Scientific

Management. Taylor's theory linked

employee motivation with organizational

profit and monetary rewards: when

employees produce more, they increase

the organization's profits and, in

return, make more money (Taylor, 1911).

In 1959, Erving Goffman, a sociologist

and writer, was the first to describe

the act of engaging in the workplace

in his book The Presentation of Self

in Everyday Life (Shanmugan &

Krishnaveni, 2012). He used the word

"embracement" to describe

people's attachment and investment

in their jobs. Goffman (1959) defined

employee engagement (embracement)

as the "spontaneous involvement

in the role and visible investment

of attention and muscular effort"

(p. 90).

William Kahn, a pioneering researcher,

was the first to use the term "employee

engagement" in his 1990 Academy

of Management Journal article, Psychological

Conditions of Personal Engagement

and Disengagement at Work. The interview-based

study explored situations at work

when people personally engaged or

"express and employ their personal

selves" and disengaged or "withdraw

and defend their personal selves"

(Kahn, 1990, p. 693). Kahn (1990)

defined engagement as "the simultaneous

employment and expression of a person's

'preferred self' in task behaviours

that promote connections to work and

to others, personal presence, and

active full role performances"

(p. 700).

A decade later, Maslach and Schaufeli

(2001) asserted that factors that

lead to employee engagement include

a feasible workload, rewards and recognition,

a sense of control, supportive colleagues,

meaningful values, and justice.

Although employee engagement has been

identified as one of the greatest

concerns for organizations in the

coming century (Leadership Insights,

2011), recent research has indicated

that only 30% to 60% of employees

are actively engaged, making disengaged

employees "one of the biggest

threats facing businesses" (MacLeod

& Clarke, 2009; The Economist

Intelligence Unit, 2011, p. 7).

Employee Engagement in the United

Arab Emirates. Towers Watson's

2012 Global Workforce study uncovered

that 65% of employees in 28 countries

are not fully engaged in their work

and that 54% of employees in the Gulf

Cooperation Council are not engaged.

In this study which aimed to help

companies understand the factors that

affect employee performance by measuring

engagement, retention and productivity,

the 1,000 employee respondents from

UAE organizations revealed the top

five drivers of engagement in the

UAE are communication, leadership,

benefits, image, and empowerment.

These findings were corroborated by

the Kenexa Research Institute (2010)

which stated that "strengthening

leadership with messages of inspiring

and promising futures " (p. 1)

is a priority when it comes to engaging

UAE nationals (Khaleej Times, 2009

).

Organizations in the United Arab Emirates

(UAE) are taking notice of employee

engagement. In 2007, Abu Dhabi Commercial

Bank collaborated with Zarca Interactive,

a leading provider of research solutions,

to create an employee engagement survey

that was specifically designed for

the UAE (Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank,

2007)(2).

The increasing interest in employee

engagement in the UAE is also evident

in the Dubai Airports employee engagement

program that began in 2012. Dubai

Airports hired Start JudgeGill, one

of the United Kingdom's top design

agencies, to undertake an employee

engagement program to inspire and

engage their 3,400 employees from

51 different nationalities (Start

JudgeGill, 2012). This attention on

employee engagement is not unique

to the UAE as evidenced that the MENA

HR Excellence Awards has a category

for Best Employee Engagement.

Employee Disengagement. Kahn

(1990) defined employee disengagement

as "the uncoupling of selves

from work roles" (p. 694). According

to Gallup (2013), there are two types

of disengaged employees: "not

engaged" and "actively disengaged"

(p. 4). "Not engaged employees

are essentially 'checked out'. They

are sleepwalking through their workday,

putting time, but not energy or passion,

into their work. Actively disengaged

employees are not just unhappy at

work; they are busy acting out their

unhappiness. Every day, these workers

undermine what their engaged co-workers

accomplish" (Gallup, 2006). Unengaged

employees and actively disengaged

employees are emotionally disconnected

from their work and are less likely

to be productive (Ford, 2013).

A study by Dale Carnegie & Associates

(2012) stated that the number one

factor prompting disengagement is

"relationship with immediate

supervisor" (p. 2). Research

also found that lack of trust in management

is a key factor in employee disengagement

(Peoplemetrics, 2011). A study by

Right Management/Manpower reported

that 94% of employees who indicated

that organizational change was poorly

handled by management were disengaged;

good communication with employees

was a major factor in whether employees

felt the change was handled well (Peoplemetrics,

2011). A disconnection between the

employee and the organizational vision

and purpose can also cause employee

disengagement (Peoplemetrics, 2011).

According to a report by Blessing

White (2011), lack of opportunities

to grow or advance is also a major

cause of employee disengagement.

Although organizations recognize that

employee disengagement is one of their

biggest threats, only a few companies

address the problem (The Economist

Intelligence Unit, 2011). Employee

disengagement impacts employee retention

(Branham, 2005), absence rates (CBI,

2012), and decreases productivity

(Gallup, 2006).

Internal Communication

Internal communication (IC) is a powerful

tool. Bill Gates (2000) once said,

"[L]ike a human being, a company

has to have an internal communication

mechanism, a 'nervous system', to

coordinate its actions" (p. 22).

The study of IC is one of the fastest

growing areas in the communication

field (Donaldson & Eyre, 2000)

and is part of the wider field of

corporate communication (Welch &

Jackson, 2007).

Communication. Clutterbuck

and Hirst (2003) defined communication

as "meaningful interaction between

two or more people" (p. xxi).

Barrett (2006) stated, "The basis

of any relationship is communication.

Without communication - be it sign

language, body language, e-mail, or

face-to-face conversation - there

is no connection and hence no relationship"

(p. 175). According to O'Neill (2011),

Leaders use communication to establish,

build, and strengthen relationships

(or to negate or weaken them) (Collins,

2001; Denning, 2007; Rowe, 1990) and

from this to influence follower feelings,

beliefs, thoughts, and practice. Flanagin

and Waldeck (2004) positioned communication

as essential for affiliation building

in organizations. (p. 38)

Lauring (2011) wrote,

[C]ommunication is a mechanism through

which groups are created, maintained

and modified (Scott, 1997)...In other

words, not only the level of comprehension

but also the intentions and positions

of groups and individuals affect the

sharing of information and the building

of relationships that could be the

outcome of a communicative encounter

(see Battilana, 2006). Accordingly,

effective communication depends not

only on the skills of organization

members but also on group and intergroup

dynamics (Weick, Sutcliffe, &

Obstfeld, 2005). (p. 235)

Researchers posit communication happens

on two-levels: the content/cognitive

and the relational/affective (Hall

& Lord, 1995; Madlock, 2008).

The content levels of a message communicate

information while its relational levels

communicate feelings (Adler &

Elmhorst, 2008). The relational aspects

of a message are often conveyed non-verbally.

The content aspects of a message are

most frequently conveyed verbally.

Definition. In the business

context, IC is defined as "all

formal and informal communication

taking place internally at all levels

of an organization" (Kalla, 2005,

p. 304). Kevin Ruck (2012), founding

director of PR Academy, defined internal

communication as "corporate level

information provided to all employees

and the concurrent provision of opportunities

for all employees to have a say about

important matters that is taken seriously

by line managers and senior managers"

(para. 4).

Development. The concept of

internal communication has been around

for more than a century. The earliest

documented evidence of internal communication

in an organization dates back to the

1840s when employees developed and

distributed internal newsletters (Ruck,

2012). The introduction of the telegraph

in the 1830s and the telephone in

the 1870s changed the pace of internal

communication by supplanting slower

channels of communication (Luther,

2009) such as post-by-sea, horse,

and carrier pigeon (Luther, 2009).

From the 1840s to the1940s, internal

communication was predominated by

internal newsletters and magazines

with articles by top management (Ruck,

2013). A top-to-bottom, one-way communication

model prevailed, where information

cascaded down to employees, and the

upward movement of ideas from junior

employees was stymied.

In 1942, the first book on internal

communication, Sharing Information

with Employees by Heron, was published

(CiprinsideUK, 2012). Heron (1942)

wrote,

the first element [in sharing information]…

is the understanding by employees

that facts about the enterprise are

not being concealed from them. The

knowledge that they can get the information

they want is more important than any

actual information that can be given

to them…the program should be

a continuous one, a method of conduct

rather than a campaign… it must

not become an institution apart from

the actual work or operation of the

enterprise. (p. 75)

The idea of two-way communication

between employees and their employer

proposed by Heron is applicable and

encouraged today.

In the 1990s, new tools for internal

communications emerged. Senior executives

started using town hall meetings,

voicemail and e-mail to communicate

with stakeholders (Luther, 2009).

Organizations are now using instant

messaging for departmental and informal

internal communication (Vanover, 2008);

recent advancements in technologies

have resulted in the rise of new internal

communication channels (Horomia, 2007).

The Internet facilitates a two-way

communication model (Luther, 2009).

Recently, Internal Communications

in many organizations have moved from

being part of the Human Resources

department to directly reporting to

top management (Luther, 2009). This

is evidence of a change in perception

of the importance of internal communication.

David Ferrabee, the Managing Director

of Change and Internal Communications

at Hill & Knowlton, recognized

this shift in the role of internal

communications: "15-20 years

ago very few businesses had someone

in the company with 'Internal Communications'

in their title. Today almost all FTSE

100 (Financial Times Stock Exchange

Index) firms do. And Fortune 500,

too" (Luther, 2009 , Recent Past

section, para. 1).

Channels. The channel is the

medium used by the sender to send

the message. Media richness theory

(MRT) implies that channels can be

ranked according to their degree of

richness (Daft & Lengel, 1986).

Channel richness is the medium's capability

to carry "multiple communication

cues, provide instant feedback, and

offer a personal focus to the communication"

(Sullivan, 1995, p. 49). Flatley (1999)

stated, "Media richness theory

ranks communication channels along

a continuum of richness, defining

highly rich channels as those handling

multiple inherent cues simultaneously,

such as using feedback, nonverbal

cues, and several senses simultaneously"

(p. 1).

Social presence theory (SPT) builds

on the richness concept of the MRT.

It adds "the perception of the

people who use the media and their

evaluations of the "social presence"

of each channel" (Sullivan, 1995,

p. 50). Researchers note social presence

is the ability of a channel to support

the social relationship between interactants

(Short, Williams, & Christie,

1976). Social presence theory assumes

that interactants value a channel

according to its 'psychological closeness'.

According to Kurpitz and Cowell (2011),

[S]ocial presence refers to the degree

to which a medium conveys the psychological

perception that other people are physically

present and suggests that media that

are capable of providing a greater

sense of intimacy and immediacy will

be perceived as having a greater degree

of social presence (Short et al.,

1976). (p. 58)

According to Rice (1993), Media Appropriateness

integrates channel richness and social

presence. The purpose of this theory

is to predict channel use. Rice (1993)

ranked media appropriateness from

most to least to be face-to-face,

telephone, video, letter and email.

Researchers have concurred that channel

features are not objective but subjective

and are shaped through the interactants'

experience with the channel, the topic,

the context, and other interactants

(Carlson & Zmud, 1999). D'Urso

and Rains (2008) stated that these

four areas impact user's views of

channel richness. O'Neill (2011) noted

that choosing the channel of communication

depends on the message, the sender,

and the target audience.

Channels of communication include

face-to-face, telephone, voice mail,

email, letters, presentations, reports,

and intranet.

Face-to-face. This communication

channel is considered the richest

information channel "because

a person can perceive verbal and nonverbal

communication, including posture,

gestures, tone of voice, and eye contact,

which can aid the perceiver in understanding

the message being sent" (Waltman,

2011, n.p.). This channel conveys

the greatest quantity of communication

data.

A study by Dewhirst in 1971 found

that face-to-face communication was

preferred over written communication.

This channel is considered effective

for reducing communication breakdown

because "in face-to-face conversation,

feedback is more easily perceived"

(Debashish & Das, 2009, p. 38).

O'Neill (2011) stated that Emirati

females have a preference for face-to-face

communication because it was the fastest

medium and decreases communication

breakdown. A study by Pascoe (2013)

in Qatar explored the link between

internal communication and employee

engagement; it stated that face-to-face

comunication was the most preferred

way of personal business communication.

Telephone. The telephone is

an oral channel. The telephone is

a communication channel that is widely

used and considered an information

rich channel. It provides similar

benefits of face-to-face but not the

visual cues.

A study by Morley and Stephenson in

1969 concluded that arguments were

more successfully presented over the

telephone than face-to-face. This

channel shares the same benefits as

face-to-face and "reduces time-space

constraints" (O'Neill, 2011,

p. 47). Researchers noticed "fewer

interruptions, shorter pauses, shorter

utterances, less filled pauses, and

a greater amount of speech in telephone

than in the face-to-face channel"

(Housel & Davis, 1977, p. 51).

Participants in O'Neill's 2011 study

of Emirati females stated that this

channel provided instanteous feedback.

Voice mail. Voice mail is considered

suitable for sending short messages

that do not require instant feedback

(Reinsch & Beswick, 1990). This

channel is also useful when the sender

wants to avoid contact with the receiver

(Hiemstra, 1982).

Email. Email is the most common

written communication channel in the

workplace and the second most frequently

used channel (Barrett, 2006). This

channel's main advantage is its speed

of transmission (Berry, 2011); email

can "carry more information faster,

at a lower cost, and to more people

while also offering increased data

communality" (Flanagin &

Waldeck, 2004, p. 142). Berry (2011)

asserted that email enables documentation

because of its archiving features.

A study in 1984 by Trauth, Kwan and

Barber concluded that "a major

reason to employ electronic messaging

systems is to increase productivity

among knowledge workers by increasing

the efficiency and effectiveness of

internal communications" as it

enhances the flow of communication

(p. 124). On the other hand, email

lacks non-verbal cues. Non-verbal

cues are a key way to determine the

affective aspects of a message (Alder

& Elmhorst, 2008). Stevens and

McElhill (2000) stated, "written

communication is not the best medium

for transmitting messages in every

situation and it is often not the

best way to motivate employees. Yet

email is often employed as if it was

the most effective medium for every

occasion as though it should automatically

motivate and engage employees"

(n.p). According to O'Neill (2011),

Emiratis females reported that email

is the most frequently used communication

channel. The participants in O'Neill's

study stated that email communication

could be used for (a) archiving meetings

or as a reference for employees who

may not recall accurately, (b) archiving

for organizational documents such

as performance evaluations, (c) archiving

for defensive mechanisms when the

participants were accused of wrongdoing,

(d) providing detailed information,

(e) increasing transparency, (f) creating

an esprit de corps by increasing awareness

of team member's tasks, and (g) enhancing

productivity by creating awareness

of all activities so that employees

are aware if there are areas of overlap.

Pascoe (2013) stated that email was

the most preferred communication channel.

Summary. A study by Newsweaver

stated that face-to-face, intranet,

and email are the most used internal

communications channels (2013). The

study reported that the use of print

publication has decreased.

Choosing the appropriate communication

channel is essential as it impacts

the effectiveness of communication.

Barry and Fulmer (2004) asserted congruence

between the communication goal (e.g.,

relationship building, information

exchange, sender ease) and the channel

employed is key to effective communication.

Short et al (1976) indicated different

tasks (e.g., information exchange,

conflict resolution, decision making)

need different channels. Sullivan

(1995) observed that preferences were

related to the type of task and in

some situations email was preferred

over oral communication channels.

Jones and Pittman (1982) indicated

the nature of the task impacts channel

selection. For example, motivating

an employee may require an inspirational

appeal to induce the employee's emotion;

this will need a channel that is rich

in non-verbal cues like face-to-face.

Reinsch and Beswick (1990) asserted

rich channels support social relationships;

therefore, when a relationship is

important, richer channels should

be used. In line with MRT and SPT,

Berk and Clampitt (1991) supported

the use of oral channels for relational

messages and written channels for

content-orient messages. Berk and

Clampitt (1991) asserted, "Because

communication channels have certain

attributes, senders must be sure that

their intentions are congruent with

the dynamics of the channel"

(p. 3). In agreement, Kurpitz and

Cowell (2011) noted, "some media

(e.g., videoconferencing or telephone)

have greater social presence than

others (e.g., e-mail), and the use

of media higher in social presence

should be important for social tasks

such as building relationships (Robert

& Dennis, 2005)" (p. 58).

In Kurpitz and Cowell's 2011 study,

subordinates identified specific types

of messages require specific channels.

For example, participants believed

confidential information should be

communicated face-to-face (Kurpitz

& Cowell, 2011).

Channel selection is important because

media choice has been shown to impact

organizational performance (Markus,

1994). Reinsch and Beswick (1990)

remarked, "Decisions about channel

are important since they help determine

the impact of specific messages and

the effectiveness of message initiators.

In the aggregate, such decisions help

shape the effectiveness, efficiency,

and ambience of an organization"

(p. 801). The 2013 Newsweaver study

also revealed that the most effective

internal communication channels are

intranet, email, and face-to-face

communication.

Culture

Lustig and Koester (1999) have posited,

"People from different cultures

whenever the degree of difference

between them is sufficiently large

and important that it creates dissmilar

interpretations and expectations about

what are regarded as competent communication

behaviours (p. 58). Research also

confirmed that when interactants have

"different paradigms, norms,

standards, and values", they

have different cultures (Phan, Siegel,

& Wright, 2009; p331). Jameson

(2007) asserted that culture should

include culture groups such as vocation

and generation.

According to Edward Hall (1959), "Culture

is communication and communication

is culture" (p. 169), where differences

in communication styles represent

different cultural frameworks (Adler

& Elmhorst, 2008). Research indicated

that cultural values influence communication

behaviors (Morand, 2003). This notion

is supported by the link between individualist/collectivist

cultures (Hofstede, 1980) and high-context/low-context

communication cultures (Hall, 1976).

Individualist cultures have a preference

for low context communication while

collectivist cultures tend to prefer

high-context communication. Thomas

(2008) asserted, "[C]ollective

cultures are 'High Context', that

is, more implicitly expressed through

intonation, euphemism and body language

than in the coded explicit part of

the message (Hall 1976; Hofstede 1997;

Loosemore 1999)" (p. 86).

Limaye and Victor (1991) noted,

Japan, which has access to the latest

communication technologies, relies

more on face-to-face or oral communication

than the written mode. We think that

the determining factor is not the

degree of industrialization, but whether

the country falls into low-context

or high context cultures as Edward

Hall defines the categories (Hall,

1959). (p. 286)

O'Neill (2011) stated, "Culture

also shapes perceptions of channels

and channel features and consequently

selection and use" (p. 75). Following

this, it is safe to assume that national-level

culture norms will influence channel

selection. For instance, groups from

collectivist cultures demonstrate

a greater preference for rich and

high social presence channels than

groups from individualist cultures

(Hara, Shachaf, & Hew, 2007).

Generation. It is widely known

that people from the same generation

often share the same cultural value,

beliefs and expectations (Kuppershmidt,

2000; Twenge & Campbell, 2008).

Walker (2009) asserted, "Gen

Y prefer to communicate synchronously"

(p. 3). Research stated that Generation

Y employees prefer more direct communication

(Johnson Controls, 2010). Limaye and

Victor (1991) asserted different perceptions

of time influence perceptions of immediacy

of feedback.

Gender. Researchers have postulated

the difference between males and females

can be so great that males and females

can be belonging to different cultures

(Maltz & Borker, 1982; O'Neill,

2011). Research indicated that men

and women communicate differently

(Tannen, 1986, 1990, 1994, 1996) because,

as children, they are socialized to

do so (Maltz &Borker, 1982). Several

researchers proved that men and women

are culturally different (Borisoff

& Merril, 1992; Gilligan, 1982;

Lakoff, 1975; O'Neill, 2011). Studies

on gender and channel use have been

scant (O'Neill, 2011). However, a

study by Lind in 2001 established,

"Communication channel richness

does appear to have cultural/gender

differences which in turn lead to

differences in channel usage"

(p. 238). Gefen and Straub's (1997)

study of three nations (Japan, USA,

and Switzerland) found that female

and male perceptions of email varied

but not their use.

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE), formerly

known as the Trucial States, is a

federation that consists of seven

Emirates: Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah,

Ajman, Um al-Qaiwain, Ras al-Khaima,

and Fujairah. Abu Dhabi is the largest

emirate, covering 87% of the total

area of the UAE (Abu Dhabi Government,

n.d). The UAE was formed in 1971 after

gaining independence from Britain.

Oil and gas are major drivers of the

UAE's economy. Nearly 25% of the country's

GDP is based on oil and gas output

(Central Intelligence Agency, 2013).

Abu Dhabi, the capital of the UAE,

controls approximately 90% of the

country's oil and gas reserves (Ministry

of Finance and Industry, n.d).

The population of the UAE in 2010

was 8.264 million with only 11.4%

being Emirati (UAEInteract, 2011).

In mid-2012, the population of Abu

Dhabi was 2.33 million; only 476,722

(20.4%) people were Emiratis (UAE

Interact, 2013).

Hofstede (1980) categorized the UAE's

culture as a collectivist one. Thomas

(2008) noted,

Within the United Arab Emirates, it

is claimed that legitimacy of a ruler

derives from consensus and consent,

and the principal of consultation

or shura is an essential part of that

system (Ministry of Information and

Culture, 2000). The operationalization

of consensus and consent has traditionally

taken place in the 'majlis' (meeting

place, council or sitting room) common

in Arab cultures (Ministry of Information

and Culture 2000; Winslow, Honein,

and Elzubeir 2002). In the 'majlis

'leaders may hold an 'openhouse' discussion

forum where individuals may forward

views for discussion and consideration

(Ministry of Information and Culture

2000). This process has also been

observed more broadly in collective

cultures whereby opinion on new issues

is formed in family conferences (Hofstede

1997, 59). (p. 85)

This demonstrates that Emiratis expect

to be a part of the decision making

process. This notion has been reinforced

by researchers from the region such

as Abdalla and Al-Humoud (2001), who

asserted, "Gulf societies endorse

typical collective values and practices

such as preference for personalised

relationships, broad and profound

influence of in-group on its members,

and limited cooperation with other

groups" (p. 511).

According to Edward Hall (1976), the

United Arab Emirates can be considered

a high-context communication culture.

Thomas (2008) posited,

Firstly, it is claimed that an oral

tradition exists in the UAE (Winslow,

Honein, and Elzubeir 2002) over a

written tradition and that an informal,

communal, 'majlis setting may best

support such a tradition. Secondly,

it has been noted that collective

cultures are 'High Context', that

is, more implicitly expressed through

intonation, euphemism and body language

than in the coded explicit part of

the message (Hall 1976; Hofstede 1997;

Loosemore 1999). Communications are

therefore 'integrally linked to the

context of relationships within which

they occur, including the history

of the interactants, their common

ground of shared understandings and

the setting of the interaction' (Smith,

Bond, and Kagitcibasi 2006, 153).

(p. 86)

Internal Communication in the United

Arab Emirates. A study conducted

by a leading communications consultancy,

Hill & Knowlton, and published

in Middle East Corporate Reputation

Watch 2008 surveyed more than 500

managers and employees in the Gulf

Cooperation Council. CEO of Hill &

Knowlton Middle East, Dave Robinson,

commented on the study indicating

that organizations in the UAE need

to work better on effectively structuring

their internal communication departments

in order to improve employee morale

and productivity (AMEinfo, 2008).

The study revealed the following key

findings about communication in organizations

in the UAE:

• 54% of employees feel that

their organization's business objectives

are clearly explained to them

• 49% of employees feel that

they do not receive the information

they need to do their job

• 25% of managers believe that

it is not necessary for employees

to fully understand how their job

relates to the organization's objectives

• 47% of employees rely on external

sources for information about their

job

• 7% of managers are not aware

who is responsible for internal communication

in their organization

The UAE government has recently started

concentrating on internal communication.

In 2008, the Government Communication

Office in the Ministry of Cabinet

Affairs launched its Internal Communications

Manual to promote consistent and clear

communication in UAE Federal Government

entities (UAE Interact, 2008). The

manual included guidelines on strategy

development, key messages, policies

and procedures, email templates, and

communication channels and tactics.

The Minister of Cabinet Affairs, His

Excellency Mohammad Al Gergawi, said,

"[T]he Internal Communications

Manual will generate positive results

in raising the overall performance

standards of the government"

(UAE Interact, 2008). The Secretary

General of the Ministry of Cabinet

Affairs, Najla Al Awar, announced

the UAE is particularly enthusiastic

about increasing employees' involvement

through timely internal communications

that update them on organizational

developments (UAE Interact, 2008).

Al Awar indicated that the Internal

Communications Manual will serve as

a catalyst for effective engagement

and interaction between all employees

(UAE Interact, 2008).

Employee Engagement and Internal

Communication

Research has shown internal communication

is a key driver of employee engagement

(MacLeod & Clarke, 2009; CIPD,

2012; Ruck, 2012). According to Towers

Watson (2010), internal communication

is one way to connect an organization

to its employees and also to connect

employees who are generationally and

culturally different. Bleeker and

Hill (2013) asserted that good internal

communication in an organization can

motivate and engage employees because

IC delivers a 'clear line of sight',

creates employee engagement, effects

the external reputation of the organization,

allows employees to understand what

changes are happening and how they

should respond, and provides regulation

and compliance because employees will

be aware of all the rules and regulations.

It is important for organizations

to be aware of the factors and tools

that engage employees (Accor Services

, 2008). Gallup (2008, 2010, 2012)

found the following communicative

activities to be key drivers to employee

engagement

• Encouragement from superiors

• Praise and recognition

• Well-defined job expectations

Powis (2012) affirmed that employee

engagement is the result of several

financial and non-financial factors,

one being internal communication in

the form of recognition. The top drivers

of employee engagement acknowledged

by the Chartered Institute of Personnel

and Development (CIPD) emphasize the

importance of internal communication

in employee engagement. According

to CIPD (2012), the two top drivers

of employee engagement are having

opportunities to communicate upwards

and feeling well informed about organizational

developments. Managers' abilities

to communicate internally are considered

key predictors of employee engagement

(Barrett, 2006; McKinsey, 2010; Welch,

2011; The Economist Intelligence Unit,

2011; Xu & Thomas, 2011; CIPD,

2012). Multiple research has proven

that a manager's ability to effectively

communicate with employees along with

encouraging two-way communication

is more important than pay and benefits

to create employee engagement (Hertzberg,

1959; Clutterbuck & Hirst, 2002;

Barrett, 2006; CIPD, 2012; Jelf Group,

2013).

3: Methodology

The purpose of this exploratory study

was to further understanding of, and

contribute to, the scant research

on employee engagement and internal

communication in the United Arab Emirates.

The study aimed to determine (a) which

internal communication channels contribute

to engaged employees' sense of engagement

and (b) how these channels do this.

Data were collected via a one-hour

long interview with each participant.

Open-ended, semi-structured questions

were used to gather participants'

points-of-view.

Data were analyzed for thematic content.

The goal of the analysis was to ascertain

which communication channels engaged

participants and the reasons they

had for choosing these communication

channels.

This chapter begins with discussion

of methodological fit followed by

a review of interview-based research

methods. The chapter ends with a presentation

of the methods utilized in this study

including data collection, instrumentation

and ethical concerns.

Methodological Fit

One-to-one, face-to-face, semi-structured

interviews were the primary method

of data collection.

Cachia and Millward (2011) asserted

that face-to-face interviews are "long

established as the leading means of

conducting qualitative research"

(p. 265). Krueger and Casey (2009)

indicated that interviews "can

provide insight into complicated topics

when opinions or attitudes are conditional

or when the area of concern relates

to a multifaceted behavior or motivation"

(p. 19).

Advantages of the interview format

used include

• researcher access to communication

rich elements that provide social

cues such as body language, hand gestures

and voice tone (Gable, 1994; Opdenakker,

2006; Conrad & Poole, 2012)

• participant involvement on

the intellectual and emotional levels

(Byres & Wilcox, 1991; Fontana

& Frey, 2005; O'Neill, 2011)

• data depth (Stokes & Bergin,

2006; O'Neill, 2011)

• plasticity in questioning (O'Neill,

2011)

• discreetness that supports

psychological safety for participants

(O'Neill, 2011)

• flexibility of time

Krueger and Casey (2009) noted "[t]he

open-ended approach allows the subject

ample opportunity to comment, to explain

and to share experiences and attitudes"

(p. 3) and it allows "individuals

to respond without setting boundaries

or providing them clues for potential

response categories" (p. 3).

As such, interviews "contribute

to the emergence of a more complete

picture of the participants' working

environment and their everyday practices"

(Schnurr, 2009, p.18).

The disadvantages and limitations

of the interview format employed include

(a) the possibility of non-conformity

between interviews (Wimpenny &

Gass, 2000), (b) limiting relevant

information from emerging due to over-structuring

of the interview (Charmaz, 1994),

(c) lack of generalizability (Fontana

& Frey, 2005; Krueger & Casey,

2009; Stokes & Bergin, 2006; O'Neill,

2011), and (d) selection bias.

The study aimed to use the participants'

perceptions to develop an understanding

of which internal communication channels

engage employees and how these channels

promote employee engagement. A review

of the literature showed that interview-based

methods were parallel to the aims

of the study. This assertion is supported

as William Kahn, who wrote the seminal

article on employee engagement, used

the interview method in his groundbreaking

1990 Academy of Management study.

A review of the socio-cultural context

corroborated the use of the interview

method. The one-to-one, face-to-face,

researcher-respondent interview fits

the socio-cultural needs of participants

from honor-based cultures such as

Emiratis. O'Neill (2011) posited,

"Three aspects of the interview

method salient to interview-based

research conducted in honor-based

cultures such as the United Arab Emirates

are: psychological safety, depth,

and flexibility" (p. 97). Haring

(2008) noted, "Qualitative methodology

is especially useful in areas where

there are limitations in the market

knowledge base. These include small,

close-knit communities". These

descriptors have been applied to the

UAE by a variety of noted researchers

such as Bristol-Rhys (2010).

Participants

The screens for participant eligibility

were (a) ability to participate in

English; (b) above 18 years of age

and below 60 years; (c) Emirati; (d)

working in the organization for more

than six months; (e) willingness to

participate in one face-to-face interview;

(f) willingness to have their contributions

to the study publicly disseminated;

(g) at least a high-school graduate;

and (h) identification as an engaged

employee. Because I had an existing

professional relationship with the

participants, I was able to identify

engaged employees.

The participant group consisted of

sixteen Emiratis that are employed

at a federal organization in the UAE:

four females and four males; five

from Generation X (people born between

1964-1978) and eleven from Generation

Y (people born between 1979-1991).

Each participant was given an informed

consent form, which had been approved

by Zayed University's Institutional

Research Review Board for ethical

clearance. The form stated the topic

of the study (the link between employee

engagement and internal communication).

It also indicated that participants

were not required to participate,

and, if they did participate, they

could withdraw from the study at any

time without penalty. All participants

of the study signed the form and participated

fully.

Sampling

Although the research sample was small

(N=16), Marshall (1996) indicated

this does not necessarily affect validity

or reliability in qualitative studies,

"….an appropriate size for

a qualitative study is one that adequately

answers the research question"

(p. 523).

The sampling method was non-random,

convenience sampling. Convenience

sampling is the intentional choice

of an informant because of their qualities,

which allows the researcher to source

people who are knowledgeable and willing

to provide information (Tongco, 2007).

Due to the size and nature of the

organization as well as socio-cultural

factors that inhibit participation

in research and the specificity of

the screens, convenience sampling

was the most appropriate option. Employees

with whom the researcher had an existing

relationship (that encouraged openness,

honesty and disclosure) and who were

identified as engaged were targeted

for selection. Marshall (1996) noted,

"Qualitative researchers recognize

that some informants are 'richer'

that others and that these people

are more likely to provide insight

and understanding for the researcher.

Choosing someone at random to answer

a qualitative question would be analogous

to randomly asking a passer-by how

to repair a broken down car, rather

than asking a garage mechanic-the

former might have a good stab, but

asking the latter is likely to be

more productive" (p. 523)

Tremblay (1957) affirmed that in order

to acquire that best qualitative data,

it is imperative to have the best

'informants'.

Research Site

The organization currently employs

approximately one hundred and sixty

employees. It is a government organization

that is high-security. It is physically

compact. It is situated in one floor

but in two separate buildings. The

physical location of the interview

is a critical element that needed

to be addressed. Robert Merton indicated,

"[P]eople revealed sensitive

information when they felt they were

in a safe, comfortable place with

people like themselves" (as cited

in Krueger & Casey, 2009, p. 3).

For this reason, and to maintain confidentiality,

the interviews took place in a secluded

but familiar meeting room within the

workplace. As the findings of the

study directly relate to the success

of the organization and fell under

the purview of the researcher's duties

at the organization, permission was

given to interview the participants

on the premises during working hours.

The Internal Communication function

in the organization is located within

the Communication Department. The

organization employs the usual internal

communication channels such as email,

a quarterly internal newsletter, plasma

screen notice boards, intranet postings,

posters, and occasionally internal

events. In the past, the organization

had a minimum of three 'town hall'

meetings each year. The town hall

meetings still take place but are

less frequent. In addition, employees

used to independently organize weekly

lunches for all staff; however, these

no longer occur because the organization

grew.

Design

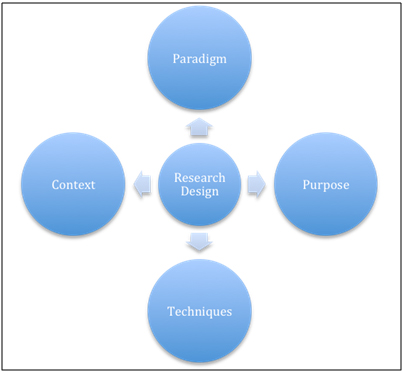

Choosing a suitable research methodology

took into account several factors

that were highlighted by Blanche,

Durrheim, and Painter (2007). The

factors included the research purpose,

theoretical paradigm, context, and

research techniques.

Phases

The study consisted of four phases:

foregrounding, pre-interview, data

collection, and member checking.

Foregrounding. To provide guidance

throughout the research, I began researching

topics related to the primary focus

of this research study approximately

two months before data collection.

Pre-interview. Before finalizing

the interview questions, the research

team reflected on question phrasing

and tips on how to get the most useful

information during interviews. The

team also conducted three mock interviews

to improve interviewing and field

note taking skills.

Figure 1: Factors of research design

(Blanche, Durrheim, & Painter,

2007)

Data Collection. The research

team opted for semi-structured interviewing

using open-ended questions to learn

about participants’ perceptions

and opinions about (a) which internal

communication channels contribute

to engaged employees’ sense of

engagement and (b) how these channels

do this. Participants were sent the

informed consent form one week prior

to their interviews. Interviews lasted

approximately one hour per participant.

All interviews took place face-to-face.

Member Checking. After the

data analysis was finalized, the data

and analysis were provided to the

participants for member checking.

Gordon (1996) emphasized the importance

of cooperation between the researcher

and participant during the data analysis

process. About one week after the

participants received the data analysis,

the participants were contacted by

telephone for their comments and feedback

on the findings.

Questions

The interview questions (Appendix

A) focused on the following: (a) which

internal communication channels contribute

to engaged employees' sense of engagement?

and (b) How these channels do this?

To generate rich data, participants

were asked a series of open-ended

questions that explored their use

of communication channels in their

day-to-day life and the workplace.

Questions at the beginning of the

interview were broad and general,

as the interview progressed, questions

began telescoping to become more focused

to the research question. The interview

questions can be categorized into

three categories; "(a) descriptive,

(b) comparative, and (c) relationship"

(Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2006, p.

480). The first set of the questions

was descriptive and focused on demographics

such as age, gender and tenure with

the organization. The second set of

questions was comparative and asked

participants to compare communication

channels that they use in their day-to-day

life and in the workplace. The final

set of questions can be categorized

as relationship questions. The final

set asked participants about the internal

communication channels that make them

feel involved and connected in the

workplace (and how) and which channels

they use when they want others to

feel involved and connected in the

workplace (and why). Each interview

began with an informal chat, participants

who had questions regarding the study

has an open opportunity to ask them

then. The concluding questions of

the interview were: 'Is there anything

we didn't talk about that you think

we should?' and 'Are there any questions

that you want us to go back and revisit'.

This was to ensure that all pertinent

information was presented.

Answers

In line with Emirati cultural mores

and to protect the participants' anonymity,

the findings were associated with

the group rather than identifiable

to particular participant. Similar

to Al Jenaibi (2010), when referring

to a contribution of a participant,

this was done using a code that has

no relation to the participants' names.

Furthermore, some data and analysis

were not included in the study to

protect the participants' identity.

Instrumentation

Field notes were used as a method

of data collection. Audio and video

recording was ruled out as an option

due to socio-cultural norms and privacy

preferences of the participants. This

decision was supported by others who

have conducted research in the region.

To encourage openness in her study

of Omani female leaders, Al Lamky

(2006) did not tape record interviews

but she did take hand-written notes

while Bristol-Rhys (2010) noted, "[T]he

women I have talked with have all

expressed their opinions quite openly,

none wanted to be identified in the

book, or indeed to be identifiable"

(p. 23). In addition, Al-Jenaibi (2010)

concluded, "Conducting research

in the UAE is often difficult…doing

interviews with many employees must

be completely confidential. For example,

many females will not provide their

names and work places in order to

be able to speak freely" (p.

72).

In addition to cultural congruence,

main advantages of field notes are

their cost, reliability, and simplicity:

no expensive equipment to purchase

and set up (O'Neill, 2011).

The disadvantages of field notes occur

in the researcher such as incomplete

recollection of the participants'

answers and bias. As mentioned by

Krueger and Casey (2009), many "don't

know how to take effective field notes.

They record impressions, interesting

ideas, perhaps a few choice words

or notes… These notes are fragmented

and incomplete for analysis"

(p. 94). Jasper (1994) noted the need

for researchers to develop skills

that enable the collection of data

without "contaminating"

(p. 311) it. Krueger and Casey (2009)

emphasized, "The interviewer

encourages comments of all types-positive

and negative. The interviewer is careful

not to make judgments about the responses

and to control body language that

might communicate approval or disapproval"

(p.6). Byres and Wilcox (1991) advised

interviewers to "refrain from

contributing to the discussion as

much as possible and monitor his or

her actions carefully" (p.69).

To accomplish this Gillham (2002)

advised that the interviewer should

be reflective and self-aware. For

this reason, the researchers engaged

in supervised practice before commencing

actual data collection from the study

participants.

There are two methods to formatting

field notes: "record notes and

quotes" (Krueger & Casey,

2009, p. 94) and "capture details

and rich descriptive information"

(Krueger & Casey, 2009, p. 94).

In the former method, key words and

quotes are recorded by the researcher

on different sides of a page. Field

notes for this study followed the

"notes and quotes" format.

In this study, both the participants

and one of the researchers were Emirati,

thus eliminating the need to employ

a cultural confederate.

Coding and analysis. The goal

of this study was: (1) identify which

internal communication channels contribute

to engaged employees' sense of engagement?

and (b) ascertain how these channels

promote engagement. The content of

participants' responses were analyzed

to meet the goals of this study. As

noted by Krueger and Casey (2009),

during analysis, not all questions

or answers are of the same value because

different questions have different

purposes. The amount of time and attention

given to each question should be comparative

to its importance to the main research

goals. Questions, such as opening

questions, do not need to be analyzed

(Krueger & Casey, 2009). In this

study, only the two main questions

were analyzed. The purpose of the

other questions was to relax the participants,

to allow them to 'warm-up' and to

stimulate their thinking about communication

channels and preferences.

Gillham (2000) indicated participant

discussion can be analyzed to determine

content, "Content analysis is

about organizing the substantive content

of the interview…there are two

essential strands to the analysis:

identifying those key, substantive

points; putting them into

categories" (p. 59). To undertake

this, a “Key Concepts” framework

was applied (Krueger & Casey,

2009, p. 125). The main purpose of

this framework was "to identify

a limited number of important ideas,

experiences, preferences that illuminate

the study" (Krueger & Casey,

2009, p. 125). As per Lincoln and

Guba's (1985) recommendation, data

were analyzed by identifying key concepts

and themes by reading and re-reading

of notes. Then, the main concepts

were coded and put into categories.

The research team developed a rank

of order of channel use for each interview

question. Channel use and justifications

could be compared across conditions.

This was the second level of analysis.

The third level of analysis was more

complex; it linked channel use and

justifications with findings from

research in the literature. It aimed

to present theoretical explanation

for channel selection.

Qualitative content analysis presented

trends of channel selection; these

were described qualitatively. The

findings in this study are presented

in narrative and statistical format

organized by question and channel.

Ethical Considerations

Two main areas that were put into

consideration while undertaking this

study: research bias and confidentiality.

To ensure the ideas presented are

the participants’ and notthose

of the researchers, the research team

self-monitored for bias. The team

also compared the data to existing

studies for congruence. Most importantly,

the research team focused on the aim

of the research “to accurately

represent the range of views”

(Krueger & Casey, 2009, p. 126).

To ensure confidentiality several

measures were put into place. Participants

were allowed to withdraw from the

study at anytime. Participants were

not required to answer a question.

Participants' answers were not audio

recorded. Participants' files were

labeled with a two-letter code unrelated

to the respondent's name. The names

of the participants were never shared.

And all data are stored securely and

require password access.

4: Presentation

of Data

The purpose of this exploratory study

was to further understanding of, and

contribute to, the scant research

on employee engagement and internal

communication in the United Arab Emirates.

The study aimed to determine which

internal communication channels contributed

to engaged employees' sense of engagement

and how these channels do this.

To obtain accurate data about the

topic of inquiry, participants described

actual internal communication channels

that they use to send and receive,

explained which channels make them

feel most connected and involved (and

how), and explained which internal

communication channels they use when

they want to make others feel connected

and involved (and why). Questions

were phrased so as not to bias participants'

responses and to gather as much information

as possible from the participants.

The categorical descriptors used throughout

the study were gender and generation.

Participants

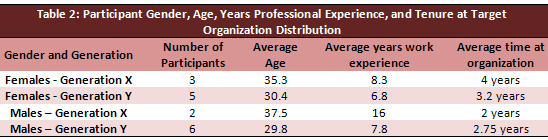

The average participant age was 32

years. The average participant age

for the female participants was 32.35

years and the average participant

age for the male participants was

31.75 years. Three females were from

Generation X (born between 1964-1978)

and five were from Generation Y (born

between 1979 and 1991). Two males

were from Generation X and six were

from Generation Y.

Only one of the participants attended

an Arabic-medium university, the remaining

15 participants attended English-medium

universities. Four of the 16 participants

attended English-medium, post-graduate

education (i.e., Masters).

The average number of years of work

experience was 8.8 with a range between

one and 18 years. The average number

of work experience for the female

participants was 7.8 years while the

average number of work experience

for the male participants was 9.8

years. The average time worked at

the federal authority during the time

of the study was 3.06 years, with

a range of 1.4 years to 5 years. The

average time worked at the federal

authority for the female participants

was 3.5 years while the average for

the male participants was 2.5 years.

Table 2 summarizes the participants'

gender, age, professional experience,

and tenure at the target organization

distribution.

Interview Questions

Questions one to seven focused on

demographics and tenure (3).

The purpose of these questions was

to develop a context. Questions eight

and nine were about the communication

channels that the participants used

in their daily life. The purpose of

these questions was to (a) stimulate

the participants' thinking, (b) relax

the participants, and (c) to get the

participants comfortable with the

interview process. Questions ten to

15 focused on the communication channels

used by the participants in the workplace.

The purpose of these questions was

to focus the participants' responses

for the following questions and to

stimulate the participants' thinking

by comparing their responses with

what they feel are engaging communication

channels. Questions 16 and 17 focused

on internal communication and engagement

in the workplace. The purpose of this

question was to determine which channels

are perceived as engaging and how.

These questions directly related to

the purpose of the study and were

the two that were the focus of analysis.

Questions 18 and 19 focused on added

channels and comments. The purpose

of these final questions was to ensure

that the participants shared all their

experiences relevant to the study.

In this section, the most frequent

communication channels that are used

to receive and send information in

the workplace are first identified.

Next, the communication channels that

the participants prefer to receive

and send information from in the workplace

are indicated. Then, the communication

channels in the workplace that make

the participants feel most involved

and connected are presented. This

is followed by the channels the participants

identified as using in the workplace

when they want to make others feel

involved and connected. Finally, the

participants stated which communication

channels they would like to see added

in the workplace.

Some participants' answers included

more than one communication channel

per question. Hence, this will yield

percentages more than 100%.

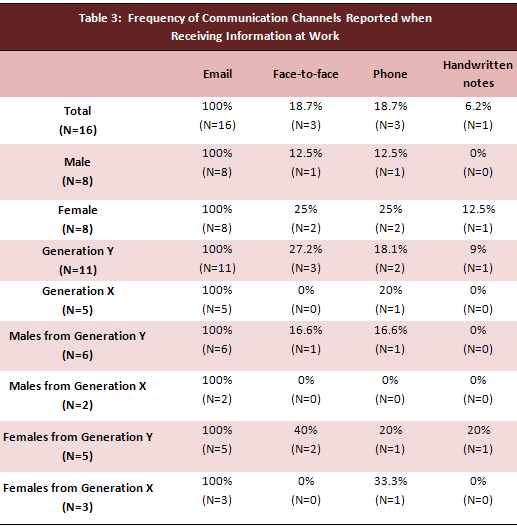

Interview question 12. What

are the most frequent ways of communication

you receive here at the organization?

The most frequent communication channel

that the participants received information

from was email. All 16 participants

stated that email was the most frequent

channel by which they receive information.

Face-to-face was the second most frequent

channel. Overall, females were twice

as likely to receive information via

face-to-face than males were (25%

v. 12.5%). Females from Generation

Y were 4 times more likely to receive

information via face-to-face than

females from Generation X (40% v.

0%). Overall, Generation Y respondents

indicated receiving information from

a wider variety of channels than Generation

X respondents (4 channels v. 2 channels).

In addition, males from Generation

Y indicated receiving information

from a wider variety of channels than

males from Generation X (3 channels

v. 1 channel). The top four answers

in each category are displayed in

Table 3.

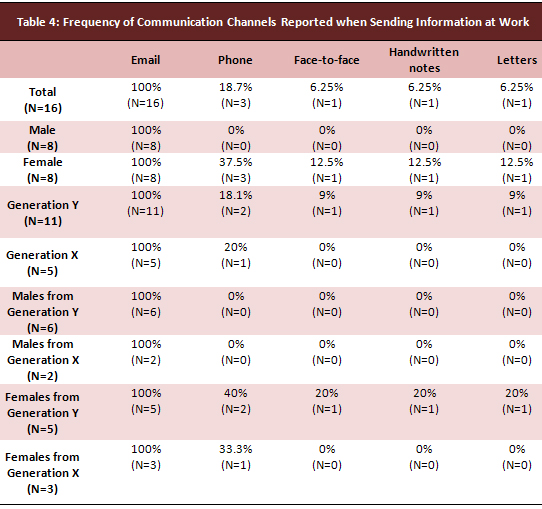

Interview question 13. What

are the most frequent ways of communication

you send here at the organization?

One hundred percent of the participants

stated that email was the most frequent

communication channel they used when

sending information in the workplace.

Males across both generations indicated

the use of email only as the most

frequent channel of communication

in the workplace. Overall, female

respondents indicated a wider variety

of most frequently used communication

channels than male respondents (5

channels v.1 channel). Similarly,

Generation Y respondents reported

a wider variety of channels than Generation

X respondents (5 channels v. 2 channels).

Female respondents from Generation

Y indicated more channels than female

respondents from Generation X (5 channels

v. 1 channel). The answers of each

category are displayed in Table 4.

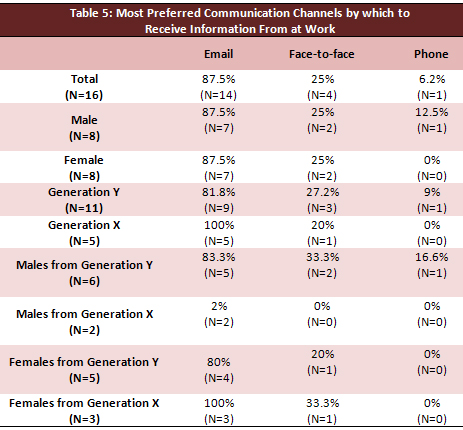

Interview question 14. Which

ways of communication do you prefer

to receive information from? Why?

The following interview question focused

on the communication channel by which

the participants prefer to receive

information from and the reasons for

this. The most common communication

channel that participants stated as

a preference to receive information

from was e-mail. Fourteen out of the

16 (87.5%) participants indicated

that their preference for email was

because of its archiving features

and speed of transmission. F5 stated,

"Email is the easiest way of

communication. I know what the requirements

are and I have the space to reply

when I can. I can use it for future

reference and especially for record

keeping. There is no time limit to

access the information. I decide when

to reply which is when I have enough

time and space". M2 noted, "Email

acts as a tracker for data, information,

saves information, provides evidence".

The notion of utilizing email for

its documentation and archiving features

was shared by M5, M6, M7, M8, F2,

and F5.

Overall, male and female respondents

indicated their preference to receive

information by email and face-to-face

equally (87.5% and 25% respectively).

Female respondents across both generations

showed preference to the same communication

channels (email and face-to-face).

Generation Y respondents indicated

a preference for phone while Generation

X respondents did not (9% v 0%). Male

respondents from Generation Y indicated

a wider variety of preference for

communication channels by which they

receive information from than male

respondents from Generation X (3 channels

v. 1 channel). The top three answers

in each category are displayed in

Table 5.

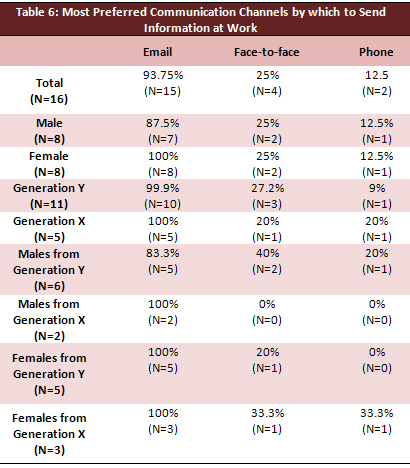

Interview question 15. Which

ways of communication do you prefer

to send information from? Why?

The most common channel the participants

preferred to send information from

was email. Their preference to email

was due to its archiving features,

accessibility, and speed of transmission.

F6 said that using email to send information

is "...precise and it is easy

to keep everyone in the loop".

M5, M6, M8, and F2 also stated the

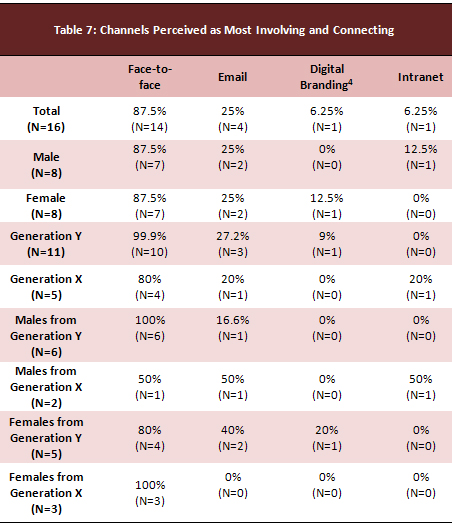

recordkeeping feature of the channel