|

Retention of knowledge within the

private sector organizations in the

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Alshanbri,

N.

Khalfan, M.

Maqsood, T.

RMIT University,

Melbourne,

Australia

Correspondence:

Malik Khalfan

RMIT University,

Melbourne,

Australia

Email: malik.khalfan@rmit.edu.au

Abstract

This paper presents a brief literature

review of knowledge and explores the

role of Knowledge Management (KM)

and Human Resources Management (HRM)

both in sustaining Intellectual Capital

(IC) within an organisation, particularly

in the context of Nitaqat Program

in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).

Based on the literature review, it

argues that a new worker could be

transformed to a knowledge-worker

if appropriate transition processes

were in place for knowledge retention

and capture from an out-going employee.

This paper presents the findings from

the interviews undertaken with both

local and non-local employees in the

private sector in KSA and reviews

the impact of Nitaqat Program resulting

in knowledge sharing and management

of sticky knowledge between non-local

employees leaving the companies and

local employees taking their positions.

Key words: Knowledge Management,

Knowledge Sharing, Human Resources

Management, Employees, Nitaqat, Kingdom

of Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Knowledge has two widely known formats

which are explicit and tacit as defined

by Polanyi (1964). Explicit knowledge

can be expressed in words and numbers.

This format can be easily shared and

transferred between people in many

forms like data, specifications, manuals,

etc. On the other hand; tacit knowledge

which is often difficult to share

or transfer comes in forms such as

insights, intuition, and hunches.

In order to transfer tacit knowledge;

it needs to be converted into an explicit

form. Nonaka (1994) identified four

possible ways for Knowledge transformation

from one form to another; these ways

are Socialization (from tacit to tacit);

Externalization (from tacit to explicit);

Internalization (from explicit to

tacit) and Combination (from explicit

to explicit). Nonaka (1994) also defined

the Externalization as the way of

converting tacit knowledge into words

or visual concepts to make it easier

to be understood. The previous methods

can transform knowledge forms from

one to another but sometimes it is

hard. When Knowledge is hard to transfer

then it is called sticky knowledge.

Eric von Hippel (1994) defined stickiness

of information as the "incremental

cost of transferring a given unit

of information in a form usable by

the recipient". Sticky Knowledge

is also defined as the knowledge that

is hard to move or costly to transfer.

Knowledge transfer has been defined

as an activity that facilitates knowledge

movement in any organization (Bou-Llusar

and Segarra-Cipres, 2006).

Knowledge stickiness has negative

effects on an organization's performance;

while the ease of knowledge transfer

can assist in: Facilitating better

organization decision-making capabilities;

Improving administrative services;

Preserving organization memory; Combating

staff turnover by facilitating knowledge

capture and transfer; Improving quality

of services, products and innovation;

Reducing 'product' development cycle

time; Reducing costs; competitive

capacity and position in the market;

increasing customer satisfaction;

employee satisfaction; communication

and knowledge sharing; and Knowledge

transparency and retention.(Kidwell

et al., 2000, Jennex et al., 2009,

Maqsood, 2006).

Szulanski studied more than 120 "best

practices" within 8 firms and

he found that the three largest contributors

to the knowledge stickiness are: The

lack of absorptive capacity by the

recipient; Causal ambiguity and the

arduous relationship between the information

source and recipient. Here is a brief

description on these factors:

Lack of absorptive capacity:

There are many matters that can increase

the capacity of the recipient in absorbing

new knowledge such as the related

prior knowledge such as the gained

educational knowledge in a selected

field and the recipient's ability

to recognize and seek sources of support

for implementing a new practice. The

lack of absorptive capacity for the

recipient is linked to knowledge stickiness

and it also can paralyse the transferring

and the applying of new knowledge.

This factor will increase costs, delay

completion and may compromise the

success of the transfer event. Therefore,

if a recipient lacks absorptive capacity,

Szulanski (1996) hypothesized stickiness

would be increased.

Casual ambiguity: the unknown

reasons or the uncertainty for knowledge

transfer's success or failure is the

main cause of causal ambiguity. Szulanski

hypothesized that the greater the

causal ambiguity the more difficult

knowledge can be transferred. Casual

ambiguity is linked to many factors

and it is mainly linked to the human

factor.

Arduous relationship: (lack

of empathy, trust or commitment to

collaborate in the task of sharing

knowledge). Transferring knowledge

depends on the interactions of two

parties and usually human factors

play a major role in these interactions

directly or indirectly. As long as

there is an intimacy and an ease of

access of communication between the

source and the recipient; transferring

knowledge wouldn't be an issue. Szulanski

(1996) mentioned that the arduous

relationship between the source and

the recipient (such as laborious and

distant) is considered a factor that

might cause the stickiness of transferring

knowledge.

Nitaqat Program

Nitaqat is a program that aims to

stimulate employment of locals in

the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It determines

the new rates of Saudisation and applies

them to all private sector enterprises.

Furthermore, it has linked these rates

with a matrix of incentives and facilities

that qualify them according to the

rates of Saudisation. The program

divides the private sector enterprises

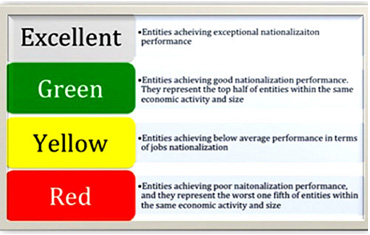

into four zones as shown in Figure

1 (excellent, green, yellow and red).

Most of them are now situated in the

green zone, which includes firms that

have achieved reasonable and acceptable

rates of employing Saudis. The enterprises

that are located in the yellow and

red zones do not employ Saudis or

their rate of Saudisation is less

than acceptable (see an example in

Figure 2). These enterprises have

been given sufficient time by the

Ministry of Labour to correct this

and move to the green and excellent-rated

zones.

Figure 1: Four categories for Nitaqat

(Source: Saudi Ministry of Labour)

Figure 2: Saudisation requirement

within four categories for Nitaqat

(Source: Saudi Ministry of Labour)

The firms that accepted Nitaqat and

entered the excellent and green zones

will be provided with an array of

facilities and motivations, making

it easier for them to deal with their

employees and workers' unions, besides

giving them sufficient flexibility

to achieve the desired levels of growth.

Furthermore, the program aims to

create a much-needed balance between

the advantages of hiring a foreign

worker and a Saudi worker by raising

the cost of maintaining foreign workers

in the red and yellow zones. Also,

Nitaqat is a monitoring tool for the

Saudi labour market, one which aims

for more localisation of jobs in the

private sector and reducing the country's

unemployment rate. In this study 45

companies located in the green, yellow,

and red zones were contacted with

an official letter from the University.

Twenty companies agreed to participate

in the study from three categories

- green, yellow and red zones. Finally,

just 13 companies were interviewed

during the given timeframe. Their

classifications are as follows: four

companies in the green zone; five

companies in the yellow zone; and

four companies in the red zone. This

paper presents the analysis and discussion

from the interviews undertaken with

local and non-local employees regarding

the implementation of Nitaqat Program

in their companies.

Research Methodology

The overall aim of the study was to

review the literature of both Knowledge

Management and Human Resources Management

in order to find the links between

both of them and using these links

to support the employee replacement

process in Saudi Arabia, specifically

with the context of the Nitaqat program.

One of the main objectives of this

research was to investigate and document

the problems or barriers that Saudi

organisations may face while enforcing

Nitaqat. This study is considered

to be a Social Constructivism Approach

(case study, descriptive study, and

exploratory research) because it seeks

to document a particular interest.

For the purpose of obtaining necessary

data, the researcher employed qualitative

research techniques. This decision

was based on the rationale and objectives

of the study, the required depth of

the investigation and dominance of

"how" and "what"

questions. The above mentioned objective

was addressed by the in-depth case

studies. Tools to collect data included

semi-structured interviews, as well

as documentation and archival analysis.

Conducted case studies consists of

interviews with HR managers and KM

experts, local employees and non-local

employees in 5 large, 5 medium-sized

and 5 small companies in order to

collect the primary data. The five

economic sectors that were explored

are: construction; wholesale and retail

trade; manufacturing; agriculture,

forests, hunting and fishing; and

transport, storage and telecommunications.

These five sectors were considered

worthy as they include the majorities

of foreign labour in the private sector

in Saudi Arabia.

In this study 45 companies located

in the green, yellow, and red zones

were contacted with an official letter

from the University. Twenty companies

agreed to participate in the study

from three categories - green, yellow

and red zones. Finally, just 13 companies

were interviewed during the given

timeframe. Their classifications are

as follows: four companies in the

green zone; five companies in the

yellow zone; and four companies in

the red zone. The qualitative data

for this research were obtained from

individual face-to-face semi-structured

interviews with Nitaqat's manager

from the Saudi's Ministry Of Labour,

13 Saudi Human Resources managers

in the Saudi's private sector, 13

local Saudi employees, and 13 non-local

employees. Secondary sources were

Ministry of Labour documents and announcements

about Nitaqat program, and articles

in Saudi Arabian major newspapers

and specialist journals or magazines.

Analysis and

Discussion of interviews with Saudi

(local) employees about the Nitaqat

Program

Local employees are the Saudi national

employees who are working in the country's

private sector. Thirteen local employees

from the private sector were interviewed:

four from green zone companies, five

from yellow zone companies, and four

from red zone companies. The participants

were asked a number of questions.

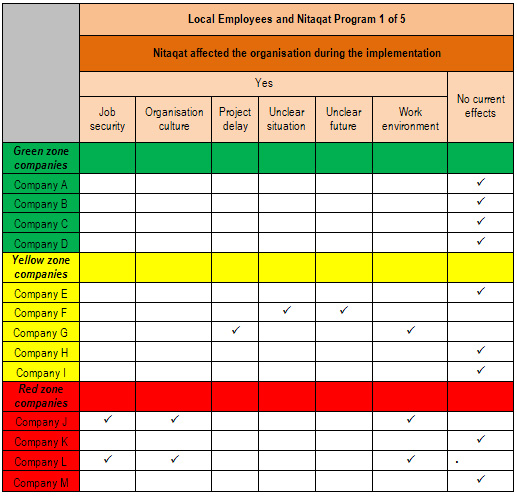

The first question was about the Nitaqat

program and whether the program affected

the organisation during the implementation.

The responses were as follows (see

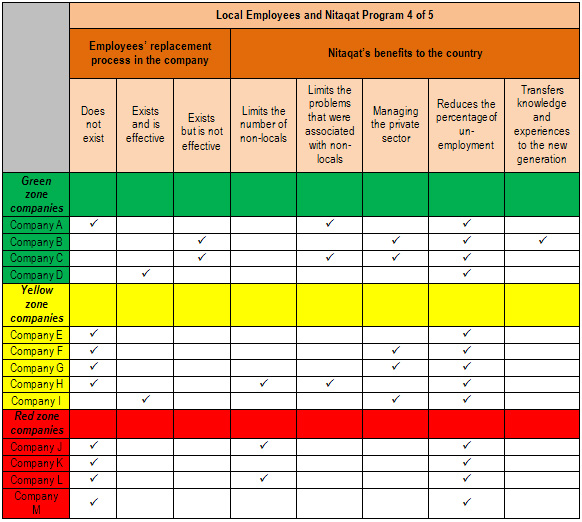

Table 1):

Table 1: Local employees and Nitaqat

program 1 of 5

• Nine local employees (four

from the green zone, three from the

yellow zone, and two from the red

zone) said that the program did not

affect the work or the organisational

performance.

• Four local employees (from

yellow zone) said it indeed affected

the organisation. One of them said

that Nitaqat's impacts were felt in

the company's workplace due to delays

in some projects. Another yellow zone

local employee, but from a different

company, stated that the program affected

the firm as it is located in the yellow

zone and the current position of the

company is not clear, which might

affect his future career in his organisation.

• The case was the same with

red zone companies. Two local employees

said that the program affected the

organisational culture and environment,

and they were currently looking for

other jobs in case their bosses could

not find a way to move the business

to the green zone.

The local employees working in the

private sector were also asked about

the benefits of the Nitaqat program

to their companies. Nine local employees

(four from the green zone, four from

yellow zone and one from the red zone)

asserted that there were some benefits

of applying Nitaqat as follows (refer

to Table 2):

Table 2: Local employees and Nitaqat

program 2 of 5

• One local employee from the

green zone said that the program helped

define the Saudi private sector by

classifying the sectors in more detail.

• Two local employees (one from

the green zone and another from the

yellow zone) said Nitaqat will create

a competitive environment and help

in securing jobs for locals in the

private sector.

• Six local employees (one from

the green zone, four employees from

the yellow zone and one from the red

zone) stated that Nitaqat will create

job opportunities for locals and thus

increase the number of Saudis in the

private sector.

• Two green zone employees commented

that Nitaqat will facilitate the MOL's

services such as renewing non-locals'

visas and issuing new ones.

• Four local employees (1 yellow

zone employee and 3 red zone employees)

stated that Nitaqat delivered no benefits

to the company.

• All local employees in the

13 companies were asked if Nitaqat

regulations were introduced to them,

to which they replied in the affirmative.

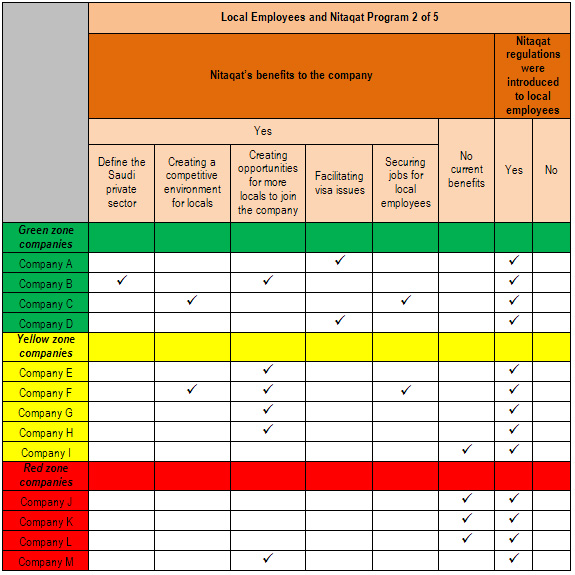

The thirteen local employees were

asked about problems in regard to

localising jobs in Saudi Arabia and

they responded with the following

answers (see Table 3):

Table 3: Local employees and Nitaqat

program 3 of 5

• Five locals (two green zone

employees, two yellow zone employees

and one red zone employee) believe

that there are no barriers to localising

all jobs in Saudi Arabia's private

sector.

• According to four locals (one

green zone employee, two yellow zone

employees and one red zone employee),

one challenge to localising jobs is

the lack of trust between senior management

and the locals; this needs to improve.

• Three locals (one local employee

from each zone) said that the nature

of the job itself was one such barrier.

They said some jobs in Saudi Arabia

will not be done by Saudis, such as

drivers or cleaners, and it is difficult

to recruit locals to carry out these

jobs. Others mentioned the odd working

hours of some jobs, such as call centre

operators.

• Two local employees (one in

the yellow zone and another one in

the red zone) believed that the time

frame that was specified by the MOL

to implement the program was too short.

• Only one local employee from

the yellow zone companies remarked

that the main barrier for localising

all jobs in the private sector was

salaries. This is because the salaries

of locals were much higher than that

of non-locals.

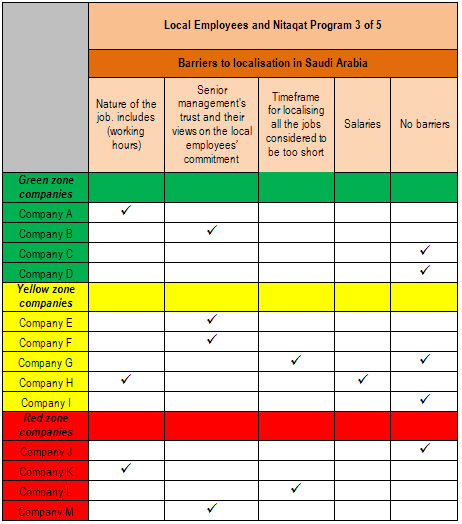

The local employees were also asked

about the barriers to localising jobs

in their companies (refer to Table

3). The answers did not differ much

from the previous question about the

barriers to localising jobs in Saudi

Arabia. Local employees in the participating

companies were also asked whether

there was an employee replacement

process in their companies. The responses

were varied (see Table 4):

Table 4: Local employees and Nitaqat

program 4 of 5

• Nine local employees (one from

the green zone, four from the yellow

zone, and four employees from the

red zone) said that there was no such

process.

• Two local employees (one from

the green zone and another one from

the yellow zone) said that the employee

replacement process did exist and

was quite effective in their workplace.

• Two local employees in the

green zone companies said the process

existed but was not effective.

Furthermore, the local employees

were asked about the benefits of the

Nitaqat program to the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia:

• All 13 local employees across

different zones said the main benefit

of applying Nitaqat was reducing the

local unemployment rate. Again, this

was not surprising as it was the main

benefit that was linked to the program

when the MOL announced it.

• Five local employees (two from

the green zone and three from the

yellow zone) said that Nitaqat will

assist in defining and organising

the Saudi private sector.

• Three locals (one from the

yellow zone and two from the red zone)

said that the program helped in limiting

and controlling the number of non-local

employees.

• Three local employees (two

from the green zone and one from the

yellow zone) said that the program

will benefit the country by limiting

the problems associated with the non-locals,

which can result from social, cultural

and religious differences.

• One local employee in a green

zone company said Nitaqat will assist

in transferring knowledge and experiences

to the new-generation local employees

in Saudi Arabia.

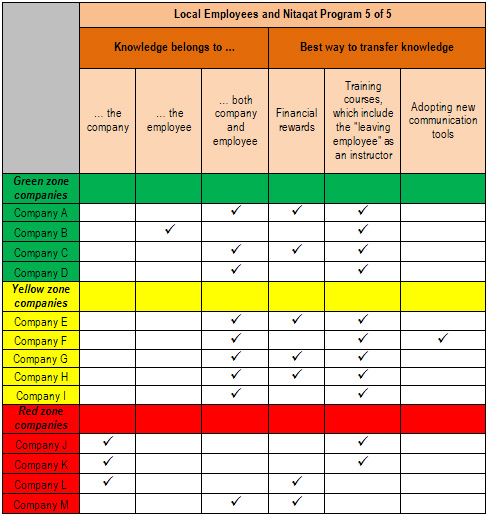

Local employees were asked if the

knowledge they had acquired during

their time with their company belonged

to them or to the company:

• Nine employees (three green

zone employees, five yellow zone employees,

and one red zone employee) said that

the knowledge belongs to both the

company and the employee.

• Three employees from the red

zone said that the knowledge belongs

to the company.

• Only one employee from the

green zone said the knowledge belonged

to him.

Furthermore, all the Saudi (local)

employees were asked about the best

way to transfer knowledge:

• Eleven Saudi employees (four

green zone employees, five yellow

zone employees, and two red zone employees)

said that the best way to transfer

knowledge was training courses that

involved the "leaving employee"

as an instructor.

• Seven Saudi employees (two

green zone employees, three yellow

zone employees, and two red zone employees)

believed the best way was to offer

financial rewards.

• One employee from the yellow

zone said that the best way to transfer

knowledge was to implement new communication

tools that could help retain essential

knowledge in one accessible place

for all employees.

Table 5: Local employees and Nitaqat

program 5 of 5

Analysis and

Discussion of interviews with Non-local

employees about the Nitaqat Program

The non-local employees

who participated in this study were

foreign employees working in the Saudi

private sector. They held an "employment

visa" enabling them to work in

their specific sector. Thirteen non-local

employees from the private sector

were interviewed: four from green

zone companies, five from yellow zone,

and four from red zone companies.

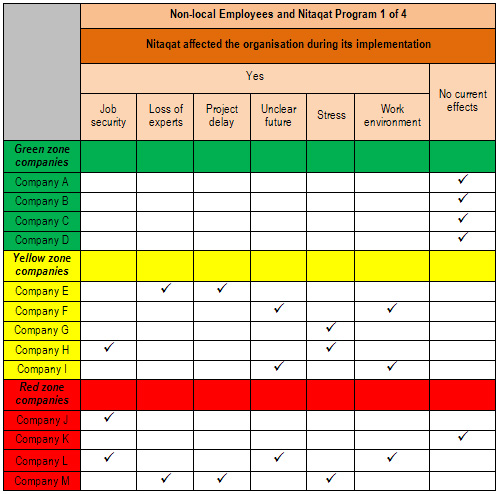

The participants were asked a number

of questions. The first question was

about the Nitaqat program and whether

the program affected the organisation

during the implementation (refer to

Table 6). Five non-local employees

(four from the green zone and one

from the red zone) said that Nitaqat

did not affect the work or the organisation's

performance. Non-local employees in

the green zone companies were not

affected by Nitaqat policies. However,

employees in the yellow and red zone

companies who have worked in the Kingdom

for six years have the right to work

for another employer in the excellent

or green zone companies as a reward

for their commitment to localisation.

This action has to be taken within

three months of the expiry of the

employment visa "Iqama"

or they will be deported. This rule

puts many non-local employees under

pressure and has led to an increase

in employee turnover in both red and

yellow zone companies.

Nine non-local employees (five from

the yellow zone and three from the

red zone) said Nitaqat affected their

business in the following ways:

• Three non-local employees (two

from the yellow zone and one from

the red zone) said that Nitaqat affected

their organisation's workplace environment.

This issue is linked with the next

point.

• Three non-local employees (two

from the yellow zone and one from

the red zone) said that Nitaqat affected

life at work by increasing the level

of stress, which led to a number of

problems for employees.

Cox and Britain (1993) define stress

as an interactive psychological state

between the individual (internal)

and the situation (external), which

can affect the individual's ability

to cope with the external situation.

Too much stress has many negative

outcomes and this issue has been discussed

by many scholars such as Cox and Britain

(1993), Cooper et al. (1996), Lazarus

(1995), Soylu (2007), and Rechter

et al. (2013). Nieuwenhuijsen et al.

(2010) and Mosadeghrad et al. (2011)

discovered evidence for a strong link

between stress, work environment,

and a number of factors including

high job demands, low job control,

low co-worker support, low supervisor

support, low procedural justice, and

low relational justice, as well as

external uncontrollable factors such

as governmental laws (for example,

the localisation program). They also

linked stress with many effects such

as turnover, absenteeism, aggression,

and hostility.

Three non-local employees (two from

the yellow zone and one from the red

zone) said Nitaqat affected the organisation's

future and made it appear uncertain.

In a recent Arab News (2014) article,

it was noted that 200,118 private

sector companies in the red zone (out

of 1.8 million companies in the private

sector) had closed down by 2013. The

MOL has confirmed this figure (MOL,

2013a). Notably, around 59% of those

firms were small and micro enterprises

that need to employ at least one Saudi

national. According to the MOL, the

number of medium-sized and large firms

that closed due to Nitaqat requirements

stood at around 200. The uncertain

future of red zone companies under

the new Nitaqat program was cited

by the non-local employees surveyed

in this study as a problematic outcome.

Table 6: Non-local employees and

Nitaqat program 1 of 4

Three non-local employees (one from

the yellow zone and two from the red

zone) said Nitaqat affected not only

the company's future but also their

job security. On this theme, a study

by Kraimer et al. (2005) found that

job security wielded an influence

on the individual employee's performance.

The study also linked employees with

low job security, and cited a negative

relationship between threat perceptions

and supervisor's rating of a worker's

job performance. Luechinger et al.

(2010) noted that the significance

of job security for the private sector

employees was higher compared to public

sector employees. The study also shows

that the subjective well-being of

private sector employees is much more

sensitive to fluctuations in unemployment

rates compared to public sector employees.

Job security in Saudi Arabia's private

sector and how the Nitaqat program

affects it needs more investigation

in the future.

Two non-local employees (one from

the yellow zone and one from the red

zone) said that Nitaqat affected the

organisation as it led to employee

turnover resulting in the loss of

experienced and expert employees.

Abbasi and Hollman (2000, p. 333)

have defined employee turnover as

"the rotation of workers around

the Labor market; between firms, jobs,

and occupations; and between the states

of employment and unemployment".

Employee turnover is always expensive

and detrimental, and affects organisational

performance (Mueller & Price,

1989). Replacing the leaving employees

and selecting, recruiting and training

new ones costs a lot of time, money,

and effort (Mossholder et al., 2005).

Park and Shaw (2013) stated that the

relationship between total turnover

and organisational performance is

significant and has negative impact.

The reasons for employee turnover

have been discussed and listed in

many previous studies (Abbasi &

Hollman, 2000; Firth et al., 2004;

Mano-Negrin & Tzafrir, 2004; Ongori,

2007). These include job stress, lack

of commitment to the organisation,

extensive job pressures, job dissatisfaction,

low wages, powerlessness, economic

reasons, organisational instability,

poor personnel, toxic workplace environment,

poor HR policies and procedures, and

lack of motivation. Ongori (2007)

showed that employee turnover imposes

many difficulties on the company's

performance and can be considered

expensive due to the hidden costs

associated with paying the leaving

employees and hiring new ones. The

Nitaqat program has caused a huge

employee turnover in red zone and

yellow zone companies. Losing the

leaving employee's knowledge is one

of the most important issues that

these companies have to consider.

Two non-local employees (one from

the yellow zone and one from the red

zone) confirmed that Nitaqat affected

their organisation's performance by

causing project delays.

Non-local employees in the private

sector were asked about the benefits

of the Nitaqat program to their companies.

These were as follows (see Table 7):

Click here for

Table

7: Non-local employees and Nitaqat

program 2 of 4ocal

employees and Nitaqat program 2 of

4

• Nine non-local employees (five

from the yellow zone and four from

the red zone) said there was no noticeable

benefit from Nitaqat to the company.

• Four from in the green zone

said Nitaqat benefited the company

by facilitating MOL processes, such

as renewal of the employment visa.

• All non-local employees in

the 13 companies were asked whether

Nitaqat regulations were introduced

to them, to which they replied in

the affirmative.

Barriers to localisation from the

non-local employees' point of view

were evident. The 13 non-local employees

were asked about these problems. Their

responses were as follows:

• Six non-local employees (two

green zone employees, two yellow zone

employees and two red zone employees)

believed that lack of expertise amongst

Saudi nationals was one of the barriers

to localising jobs.

• Five non-local employees (two

green zone employees, two yellow zone

employees, and one red zone employee)

stated that the outcomes of the education

system are not related to the requirements

of the Saudi economy.

• Five non-local employees (one

green zone employee, two yellow zone

employees and two red zone employees)

said the nature of the job itself

was one of the barriers to localisation.

They said some jobs in Saudi Arabia,

such as drivers or cleaners, would

not be done by the locals.

• One employee from the yellow

zone cited the working hours of some

jobs as a barrier as Saudis were not

willing to work for longer hours or

during night shifts.

• Five non-local employees (two

green zone employees, one yellow zone

employee and two red zone employees)

said that the major barrier to localisation

were Saudi national citizens' high

salaries.

• Four non-local employees (two

yellow zone employees and two red

zone employees) said that the commitment

of locals to private sector jobs was

questionable. They had observed that

more time and effort was required

to trust young Saudi employees.

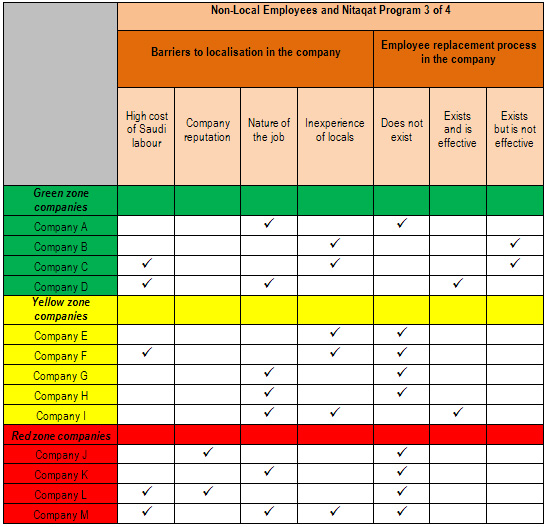

The non-local employees were asked

about the barriers to localising jobs

in the companies they were currently

working in. The answers were as follows

(see Table 8):

Table 8: Non-local employees and Nitaqat

program 3 of 4

• Seven non-local employees (two

green zone employees, three yellow

zone employees and two red zone employees)

said that the nature of the job itself

was a barrier.

• Five non-local employees (two

green zone employees, one yellow zone

employee and two red zone employees)

said that the high cost of Saudi national

employees was a barrier.

• Six non-local employees (two

green zone employees, three yellow

zone employees and one red zone employee)

commented that the inexperience of

locals was a problem.

• Two non-local employees in

the red zone companies believed that

locals did not want to work in red

zone companies.

The non-local employees in participating

companies were also asked whether

there was an employee replacement

process where they worked:

• Nine non-local employees (one

from the green zone, four from the

yellow zone and four from the red

zone) said that there was no such

process in the company.

• Two non-local employees (one

from the green zone and one from the

yellow zone) said that the employee

replacement process did exist and

was effective in their workplace.

• Two non-local employees in

the green zone companies said the

process existed but was not effective.

The non-local employees were asked

about the benefits of the Nitaqat

program to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

(see Table 9):

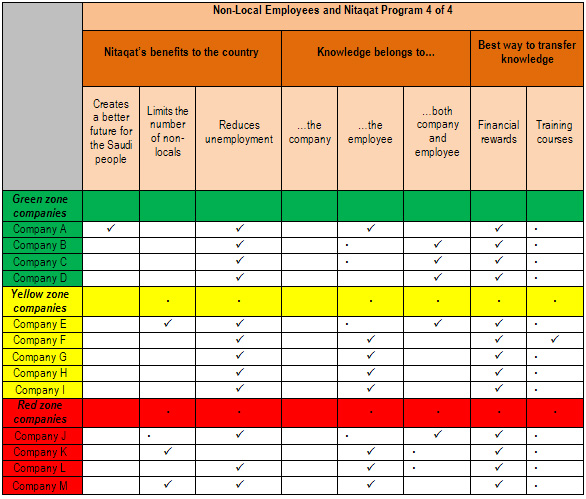

Table 9: Non-local employees and

Nitaqat program 4 of 4

• All 13 non-local employees

across different zones said that the

main benefit from applying Nitaqat

was less local unemployment. Again,

this was not surprising as the same

answer was given by the local employees.

This benefit was always what the program

intended to do when the MOL announced

it.

• Three non-local employees (one

from the yellow zone and two from

the red zone) believed that Nitaqat

helped in limiting the number of non-locals

in Saudi Arabia.

• One non-local employee from

a green zone business believed that

Nitaqat will create a better future

for Saudi youth. The employee linked

it to the huge number of currently

unemployed locals and the crimes that

idle young Saudis were committing.

The employee believed that Nitaqat

will limit such problems associated

with unemployment.

The non-local employees were also

asked whether the knowledge they had

acquired during the time they had

spent with their respective companies

belonged to them or to the company:

• Eight non-local employees (one

green zone employee, four yellow zone

employees and three red zone employees)

said the knowledge belonged to them.

• 5 non-local employees (three

green zone employees, one yellow zone

employee and one red zone employee)

said that the knowledge belonged to

the company as well as the employee

themselves.

• Remarkably, none of them considered

that the knowledge belonged to the

company.

The final question that was put forward

to all non-local employees related

to the best way to transfer the knowledge

for outgoing foreign employees to

incoming local employees. Firstly,

all non-local employees (four green

zone employees, five yellow zone employees

and four red zone employees) commented

that the best way was to offer financial

rewards. Secondly, only one non-local

employee from a yellow zone firm mentioned

training courses besides financial

rewards.

Conclusion

Recognizing that lost knowledge through

replacing employees may be a threat

to organizations and country's economy

is a critical first step in addressing

this phenomenon. Retaining the needed

knowledge in organizations relies

on people and the ability of HR departments

in changing human behaviour. The success

of this endeavour depends on the commitment

of all HR managers in collaboration

with the departing employees and the

new ones. Human Resource Departments

are playing a major role as a strategic

partner for organizations and not

as supporting administrative departments

due to their role in facilitating

knowledge between employees. This

paper may only look at a very particular

part of the problem with the current

situation in Saudi Arabia and highlights

the role of knowledge management in

facilitating knowledge sharing. The

final conclusion from the interviews

undertaken with both local and non-local

employees suggests that there were

many common themes to which all of

them agree or disagree. All the employees

from the green zone companies responded

that there was no great impact of

Nitaqat program within their organisations.

All the employees working with the

red zone companies stated that Nitaqat

brings no benefits to their organisations

and all of them were worried about

losing their jobs. Whereas, all the

employees from yellow zone companies

were unclear about the current situation

and unsure about the future of their

companies. They all stated that Nitaqat

has resulted in project delays in

their organisations. Barriers to implement

the Nitaqat program includes; education

system's outcomes that is not in line

with industries' requirements; lack

of expertise among local Saudi nationals;

commitment of local employees to private

sector; odd working hours; blue collar

nature of the certain jobs; and private

sector salaries which were much lower

than salaries awarded by public sector

for similar job description, qualification,

and experience.

References

Bou-Llusar, C.J. and Segarra-Cipres,

M. (2006) 'Strategic knowledge transfer

and its implications for competitive

advantage: an integrative conceptual

framework', Journal of Knowledge Management,

Vol. 10, No. 4, pp.100-112.

Hippel, E. V. 1994. "Sticky Information"

and the Locus of Problem Solving:

Implications for Innovation. Management

Science, 40, 429-439.

Jennex, M. E., Smolnik, S. & Croasdell,

D. T. 2009. Towards a consensus knowledge

management success definition. VINE,

39, 174- 188.

Kidwell, J. J., Linde, K. M. V. &

Johnson, S. L. 2000. Applying corporate

knowledge management practices in

higher education. Educause Quarterly,

23, 28-33.

Maqsood, T. 2006. The Role of Knowledge

Management in Supporting Innovation

and Learning in Construction. PhD

Thesis. Doctor of Philosophy, Royal

Melbourne Institute of Technology

University.

Nonaka, I. 1994. A Dynamic Theory

of Organizational Knowledge Creation.

Organization Science, 5, 14-37.

Polanyi (1964) Personal knowledge:

Towards a post-critical philosophy,

Harper & Row.

Szulanski, G. 2003. Sticky Knowledge:

Barriers to Knowing in the Firm, SAGE

Publications.

|