|

Is Marxism Still Valid in Industrial

Relations Theory?

Anam

Ullah

Correspondence:

Asm Anam Ullah

Doctoral Scholar and Academic

Macquarie University, Australia

Email: russell_adib@yahoo.com.au

Abstract

All too often, scholars are posed

with questions as to whether Marxism

has any relationships with modern

industrial relations theory. Many

say yes, many say no. However, there

is a crucial debate in the public

domain about industrial relations

theory and many try to portray it

from different analytical tools. This

short article will mediate on this

issue whether Marxism is still valid

in the current industrial relations

theory.

Key words: Marxism, Industrial

Relations Theory and Trade unions.

Introduction

"The philosophers have only

interpreted the world in various ways

but the real task is to alter it".

Karl Marx

The industrial relations (IRs) or

employment relation (ERs) theorists

have not thus far reached a certain

agreement to declare that this is

the ultimate theory of industrial

relations. Last couple of centuries

there have been many academic and

great scholars who saw industrial

relations in a different perspective.

They also tried to find the best theory

of industrial relations, but thus

far, it is most likely to see that

there is not any universal theory

of industrial relations that any potential

industrial relations student can adopt.

However, there is a significant amount

of research growing and offering different

methods of IR and ER and we can take

scholars' guideline while studying

industrial relation and employment

relations.

As an approach of Marxism in industrial

relations, a neo-Marxists interpretation

of the industrial relations or labour

process is crucial and it often conflicts

with the contemporary scholars. There

is strong debate whether Marxism is

considered as an industrial relations

theory. This short article, despite

its own limitations, the extent to

which will arrest some scholarly written

debates on these issues. Thus, theoretically

this qualitative analysis will discuss

by developing a theoretical framework

of the industrial relations theory

first, and then incorporate the scholar's

point whether Marxism is still valid

in industrial relations theory.

The Core Ideas

of Industrial Relations

The term "Industrial Relations"

(IR) has come to be established into

common use in Britain and America

during the 1920s. Initially, to some

extent, some started using IR theory

incorporating with Personal Management

(PM) and, since the 1980s, Human Resource

Management (HRM). But, interestingly,

these three have common traits in

the practical field which is based

on one single concept (management

of people) and therefore, academic

inquiries are essential in this field

(see Edwards, 2009).

Again, to avoid confusion and academic

debate, on some facets, scholars also

use "term" Employment Relations

(ER) instead of IR. Nevertheless,

some scholars try to isolate IR and

ER from a different perspective. In

saying this, again, when I went through

the scholarly written articles I strongly

found notions of IR and ER theories

and I tried to understand their basic

and fundamental differences from an

analytical observations.

Interestingly, IR, the extent to which

it covers relationships between managers

and employees is always determined

by the economic activity. This relationship

perhaps reveals a mutual understanding

between managers and employees where

economic benefits are the main agenda

of both parties. But, scholars thus

far have identified that IR theory

excludes domestic and also the self-employed

who work on their own account and

therefore they are also accountable

to maintain their own labour standards

which shows the system of self-regulation

or self-accountability.

Moreover, this concept originated

partly from the International Labour

Organization (ILO) and its European

stakeholders where Civil law is more

prominent than the Common law. Again,

according to Edward (2009), the point

is, however, when self-employed professionals

deal with customers, the extent to

which, it makes it extensively difficult

to say whether such relationship determine

the concept of "industrial relations",

but again, for understanding, potential

IR students can consider this as a

part of industrial relations when

there is a contractual agreement between

a self-employed firm and its employees

(see Edward, 2009, Eberhard, 2007;

Kaufman, 2004).

Alternatively, scholars tried to portray

the term "ER" from a different

facet. In saying this, when potential

IR or ER students try to isolate this

both from each other, to some extent,

ER theory itself focuses on: all forms

of economic activity in which certainly

all employees work under a certain

authoritative role which emerges from

the employers and therefore employees

receive wages in return for their

labour - this model represents a substantive

issue of IR system where the procedural

rule deals with conflicts between

employer and employee (see Edward,

2009; Quinlan, 2004).

Again, by the nature of the world

of work, scholars identified that

the great majority of the population

in modern times, of course, are employees

rather than employers. Some scholars

define IR theory as less effective

rather than studying all forms of

the employment relationship. But,

the debate still grows and many say

this is not to some extent a sufficient

support that contemporary observers

are trying to establish in which the

IR theory is not valid anymore, rather

scholars say it is indeed very hard

to justify the concept and implications

of IR in the current industrial studies

by grasping the narrow concept from

the economics or sociology of work

(see Eberhard, 2007; Kaufman, 2004;

Abbot, 2006).

However, whether I use the term 'employment

relations" instead of "industrial

relations", these both work on

labour regulation and scholars say

regulation comes from various sources

(see Eberhard, 2007). But there is

one common characteristic found in

scholarly written articles: employment

relations and industrial relations

deal with employer and employee and

either individually or collectively

for procedural rules or substantive

rules as these are all directly engaged

in the workplace (see Ross, 2008;

Kaufman, 2010; Chidi & Okpala,

2012).

Kaufman (2010) saw industrial relations

as the process of rulemaking for the

workplace Dunlop (1958) identified

the actors of employment or industrial

relations. Other scholars contributed

in labour regulation such as Flanders

(1965); social regulation of production

by Cox (1971); Edwards (2005) saw

the employment relationship as structured

antagonism. Social regulation of market

forces was described by Hyman (1995).

According to Bain and Clegg (1974)

cited in Chidi and Okpala (2012),

"a traditional approach to employment

and industrial relations has been

to regard it as the study of the rules

governing employment, and the ways

in which the rules are changed, interpreted

and administered".

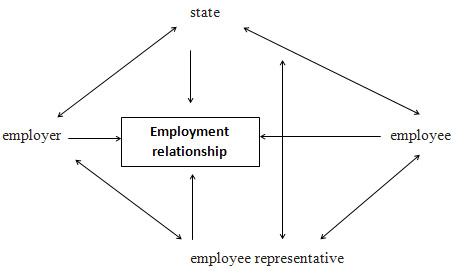

Again, Dunlop 1958; Edward (2009);

Freeman (2007); Eberhard (2007); Kaufman

(2004); Gunningham (2008); Jentsch

(2004); Johnstone (2008); Flenders

(1965); Quinlan (2004); Poole (2013);

Kittel (1967); identified three major

parties in the IR or ER system which

are (a) state (b) employer and (c)

trade union. In modern time, there

are some crucial changes in IR or

ER theories. The following model represents

the best employment relations.

Figure 1: The employment relationship

hired from Edwards, P. (Ed.). (2009).

Industrial relations: theory and practice.

The above model represents the most

common structure of employment relations

which was invented by Dunlop in 1958.

However, the contemporary IR thinkers

are offering different models of IR

and ER than the traditional concept

or models. However, to some extent,

the major parties are identified in

labour regulation by almost every

scholar, which I have already mentioned

about the three parties in the past.

Some outsourcing and external regulation

can be taken into consideration in

order to analyse the IR and ER system

in the different contexts, but as

Dunlop identified major three actors

in his (1958) IR theory, to some extent

this is still valid, but other concepts

are simultaneously considered by the

international academics and scholars

in this area.

According to Abbot (2006, p. 187):

"Work is fundamental to the

human condition. It determines what

we do for much of our waking lives

and it preoccupies much of what we

think about. It allows us to engage

with other people and it helps us

to define our sense of identity. It

provides us with access to the material

necessities of life, as well as to

the advantages and achievements of

civilisation. Its allocation, organisation,

management and reward are therefore

of no small importance. How these

are undertaken in gainful employment

tells us much about the views and

values we hold as a society. What

levels of unemployment are deemed

tolerable, what manner of work is

undertaken and how disputes between

the two sides of industry are resolved,

for example, are all matters about

which we have opinions and which are

often shaped by the prevailing cultural

boundaries, economic circumstances

and political understandings we hold

towards our engagement with work".

Indeed, for the purpose of this discussion

above, the nature of work has tremendously

changed during the last one hundred

years or so. The technological changes

made the work of the world more challenging.

People are now working in different

ambiences and employment relations

studies are now facing more challenges

to develop an appropriate theory of

ER or IR.

However, a large number of growing

research is suggesting and focusing

on the issue of industrial conflict

and meditating on this issue to solve

all the unresolved issues, but, to

some extent, there are also substantial

amounts of scholarly written articles

which have caused confusion about

the current and past IR and ER theories.

In these processes, many scholars

portrayed the IR and ER theory from

different analytical lenses, however,

it is identified that the industrial

relations theory has done so with

less uniformity and till now scholars

are introducing different ideas of

IR and ER theories according to the

context ("budgetary/market, technological

characteristics of the work place

and work community and the locus and

distribution of power in the larger

society") (see Chidi and Okpala

2012; Bray et al., 2014).

So, grounded situation is playing

a big role over the creation of IR

and ER theories. As a potential IR

and ER researcher, I found, the extent

to which, developing countries are

suffering from various issues in labour

or Occupational Health and Safety

(OHS) mainly. Western or European

countries have different labour issues

in all aspects. So, labour issues

in Common law countries and Civil

law countries have a different situation.

However, Socialist state also has

a completely different philosophy

in regards to control labour problems

than the Common or Civil law states

(Sisson & Marginson, 2001). In

addition, industrial relations has

different approaches.

Nevertheless, again, whether it is

the Common law, Civil law or a Socialist

law, one thing can be understood from

a deeper perspective that labour is

the most crucial part of their economy,

so the state needs to learn how to

develop a better labour institutions,

thus, labour issues can be identified

easily and these problems can solved

by giving an equal effort both from

academic and professional levels (see

Vogel, 2006; Guzman & Meyer, 2010).

However, as many academic scholars

have pointed out that there are distinct

approaches in the employment relationship

and these approaches are identified

from different analytical tools and

different intellectually written documents.

As I mentioned the employment relation

studies are bringing so many paradoxes

and it is not an easy way to find

which approach is being appropriate

in which context. But, to some extent,

as a potential researcher, it is my

obligation to reveal how each of these

approaches is related to the context.

But to be very specific in this article,

as I already mentioned that my analyses

will be based on a specific issue

which is (Marxism or Radicalism) and

whether there is any connection with

the current industrial relation studies

or theories, thus my next analyses

will be focusing on this particular

issue rather than discussing the other

approaches more elaborately in this

article.

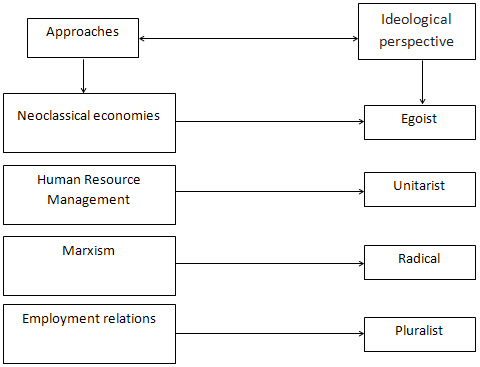

The following figure represents the

most common approaches to the employment

relationship.

Figure 2: alternative approaches

adopted from Bray et al., (2014, p.

15)

Marxist Theory

According to Chidi and Okpala (2012);

Abbot (2006); Kaufman (2004, 2010),

Marxism, however, unambiguously appeared,

more or less, to establish a general

theory of society and social change

with colossal implications for the

analysis of industrial relations within

the capitalist societies which does

not or to some extent has not any

affinities with the industrial relations

theory. Interesting indeed! In saying

so, again, scholars like Kaufman (2004)

revealed something very significant

for potential industrial relations

students; point is, however, neither

the notion of labour relations nor

the term of industrial relations,

belongs to the vocabulary of Karl

Marx (see Kaufman, 2004).

As debate grows on, more theoretically

offered an idea of such debate by

Ogunbameru (2004) cited in Chidi and

Okpala (2012), point, however, to

some extent, the application of Marxian

theory as it partly relates to industrial

relations today derives from later

Marxist scholars rather than directly

from the composition of Karl Marx

himself (see Chidi and Okpala, 2012).

Again, Kaufman (2010) pointed out

that more or less during the 1870

-1920 the industrial relations term

to some extent was originated within

a limited number of works as a response

to the worldwide "Labour Problems"

(or "Social Question") because

industrial development and industrial

society emerged at that time. Research

identifies that there was a conflict

between capitalism and socialism and

these both had revolution at that

time. Also, labour reform project

met many obstacles and objections

during that period. The world was

divided into the ideas of orthodox

classical and neoclassical economics.

According to Kaufman (2010, p. 76):

"The body of theory, largely

imported from Britain but secondarily

from France, was widely accepted,

hence establishing it as "orthodox."

The most widely accepted lesson of

orthodox economics at this time was

the principle of free trade; second

on the list was Say's Law - the contention

that a free-market system automatically

returns to an equilibrium position

of full employment. Free trade applied

first and foremost to international

exchange of goods between countries,

but the principle was extended with

only negligible qualification to domestic

and factor markets, including, most

importantly, labour markets".

Chidi and Okpala (2012) cited in Hyman

(1975, p. 12) where he defines "industrial

relations as the study of the processes

of control over work relations and

among these processes, those involving

collective worker organisation and

action are of particular concern".

Hayman known as an orthodox Marxist

has given a strong notion of industrial

relations theory - and put it this

way - Hayman asserted that this is

Dunlop and Flanders, who of them are

the giant industrial relations theorist

thus far, but again, some scholars

conceptualized the issue of industrial

relations theory which has specially

come from Dunlop (1958) and was limited

to some extent, especially finding

the actors and actor's role within

the labour or employment regulation

process. Hayman's main point, in saying

this, put it this way again, it is

almost impossible to come up with

a complete industrial relations theory

at a time rather it develops through

an on-going process and maintenance

and stability in performance in industrial

regulation is a must (Chidi &

Okpala, 2012; Hayman, 1975; Kaufman,

2004; Jentsch, 2004).

Again, Abbot (2006, p. 194) pointed

out that:

"A Marxist frame of reference

may seem redundant in view of the

break-up of the Soviet Union, the

collapse of communism in Eastern Europe

and the decline of 'radical' thinking

in the West. There are, however, a

number of studies from this school

of thought that remain influential.

This is because they are based on

vastly different assumptions about

the nature and cause of workplace

conflict, and second, because they

act as valid critiques of the previous

two frames of reference and their

associated theories. Those arguing

from a radical perspective draw principally

from the work of Karl Marx (1950,

1967, 1978), who argued that capitalist

societies were characterised by perpetual

class struggle. This struggle is caused

by inequalities in the distribution

of wealth and the skewed ownership

of the means of production. Wealth

and property ownership, he observed,

were highly concentrated in the hands

of a small number of bourgeoisie (or

capitalists), whilst the vast mass

of the proletariat (or workers) lived

in poverty and had nothing to sell

but their labour".

In saying this, once again, I need

to point Hayman's analyses in this

issue, he asserted similarly as contemporary

scholars saw the Marxist theory and

blended into different shapes.

Chidi & Okpala (2012, p, 273)

cited in Hayman (1975) in which he

asserted that:

"The Marxist perspectives

typify workplace relations as a reflection

of the incidence of societal inequalities

and the inevitable expression of this

at the work place. To sum it up, Hyman

further states that industrial relations

is all about power, interests and

conflict and that the economic, technological

and political dynamics of the broader

society inevitably shape the character

of relations among industrial relations

actors which he described as the political

economy of industrial relations. Conflict

is viewed as a disorder precursor

to change and to resolve conflict

means to change the imbalance and

inequalities in society in terms of

power and wealth. Trade unions are

viewed as employee response to capitalism".

Then, again, as a potential researcher,

to some extent, I cannot ignore saying

what other scholars identified analogously,

put this way, Marx's theory connected

with how people relate to the most

fundamental resource of all us, it

means, again, through his observation,

labour was treated as power of their

own labour. The whole, in fact, between

1844 and 1883, a period of democratic

nationalism, trade unionism and revolution

was his main theme of writing. The

labour is fundamental to Marx's theories.

Basically, Marx , for the first time

arrested a significant point in his

theory, put this way - he argued that

it is simply human nature to transform

nature, and he calls this process

of transformation "labour"

and the capacity to transform nature,

'labour power.'

However, to scholars like Kaufman

(2004), the point is, he asserted

that Marx's core institutions the

extent to which it is fundamentally

focusing on industrial relations-free

labour markets and the factory system-where

Kaufman found that the major components

of Marx's analysis of industrial capitalism,

and he was a keen observer, thus he

addressed on labour issues extensively

and mainly in trade unionism. But,

many scholars say - his main focus

was on classifying the distinct gaps

between labour and capital. Scholars

also pointed out that, he, to some

extent, albeit his ideology was based

on trade unionism, however, he could

not show how trade unions can be a

fruitful organization in terms of

obtaining the ultimate success through

the collective process in terms of

wage discriminations and other labour

issues.

But, however, the way he saw, it is

not the actual nature of trade unions

at present that we see around the

world where trade unions in many Western

and European countries are developed

as an institution. Contrarily, in

many developing countries, trade union

has not yet been treated as a supportive

force of changing the labour or OHS

conditions as they have little collective

bargaining scope and in some countries

like Cambodia, China, Bangladesh and

so on, where, to some extent, trade

union leaders are brutally killed

and tortured (see, Kaufman, 2004,

2010; Chidi & Okpala, 2012; Hayman,

1975; Abbot, 2006; Flanders, 1965;

Brown et al, 2013; Marston, 2007;

Munck, 2010: Islam & McPhail,

2011).

In saying this, many say, his main

focus on trade unions show radicalism

rather showing how they can collectively

raise their concern about the exploitation.

As we see now in many countries like

the U.K, Australia, where the labour

party represents the trade union and

trade union has been treated as one

of the crucial actors in the industrial

relations system which is absent in

the Marxist theory (see Kaufman, 2004;

Balnave et al., 2009).

Concluding remarks

But in the case of Marxism it is especially

incredible to realize that a few (only

a few now), still believe that its

promised golden age will yet arrive

as capitalism drastically grasped

the global market. Yet Marxism had

the perfect opportunity to demonstrate

its promised wonder and glory in the

Soviet and Chinese experiments in

which state-wide Marxist support was

imposed and deviating opinions banned.

What were the fruits of those experiments;

this makes another debate which is

inevitable.

Whatsoever, industrial relations system

and market system have tremendously

changed during the last one hundred

years or so, thus many believe, Marx's

theory has not yet demised indeed

as we still see huge exploitations

around the world especially where

global capital drastically took control

over the labour market. Developing

nations are suffering from inadequate

resources, thus, those developing

nations compromising with the capitalist

by offering abundant cheap labour

like Cambodia's and Bangladeshi's

garment industry where millions of

poor and rural migrated workers are

working with very low wages. Technological

changes are the major concern for

the labour at this moment as capitalists

are investing in this field. So, to

some extent, whether it is directly

related to the Marx's theory of industrial

relations, however, his labour theory

still shows huge potential for further

research in this area.

Finally, as I said, it is indeed almost

impossible to bring all the analyses

in this article as this area is quite

enormous. However, for a potential

researcher, it would be wise to consider

in order to understand Marx's theory,

whether it has any connection with

the modern form of industrial relations

theory by analysing further from his

the political economy of industrial

relations, labour process analysis,

and the French regulation school.

However, thus far, there very little

support has been identified in scholarly

written articles where Marxism has

been considered as an industrial relations

theory.

References

Abbott, K. (2006). A review of employment

relations theories and their application.

Problems and Perspectives in Management,

1(2006), 187-199.

Balnave, N., Brown, J., Maconachie,

G., & Stone, R. (2009). Employment

relations in Australia, 2nd edn, John

Wiley & Sons, Australia Ltd.

Bray, M., Waring, P., Cooper, R.,

& MacNeil, J. (2014). Employment

relations: theory and practice, 3rd

addition, McGraw-Hill, Sydney.

Brown, D., Dehejia, R., & Robertson,

R. (2013). Regulations, Monitoring,

and Working Conditions: Evidence from

Better Factories Cambodia and Better

Work Vietnam. Working paper, Tufts

University. http://users. nber. org/~

rdehejia/papers/Brown _Dehejia_Robertson_RDW.

pdf.

Chidi, C. O., & Okpala, O. P.

(2012). Theoretical Approaches to

Employment and Industrial Relations:

A Comparison of Subsisting Orthodoxies.

INTECH Open Access Publisher.

Cox, R. (1971). "Approaches to

the Futurology of Industrial Relations."

Bulletin of the

Institute of Labour Studies, Vol.

8, N0. 8, pp. 139-64.

Dunlop, J.T. (1958). Industrial Relations

Systems. New York: Holt (title now

owned by Cengage Learning)

Eberhard, A. (2007). Infrastructure

Regulation in Developing Countries:

an exploration of hybrid and transitional

models, Public-Private Infrastructure

Advisory Facility, Working paper 4.

Edwards, P. (Ed.). (2009). Industrial

relations: theory and practice. John

Wiley & Sons.

Flanders, A. (1965). Industrial Relations:

What is Wrong with the System? An

Essay on Its Theory and Future. London:

Farber & Farber.

Freeman, R. B. (2007). Labor market

institutions around the world (No.

w13242). National Bureau of Economic

Research.

Gunningham, N. (2008). Occupational

health and safety, worker participation

and the mining industry in a changing

world of work. Economic and Industrial

Democracy, Vol. 29(3), 336-361.

Guzman, A., & Meyer, T. L. (2010).

Explaining soft law. Berkeley Program

in Law & Economics.

Hyman, R. (1995). "Industrial

Relations in Theory and Practice."

European Journal of

Industrial Relations, Vol. 1, No.

1, pp. 17-46.

Hyman, R. (1975). Industrial Relations:

A Marxist Introduction. London: Macmillan.

Islam, M.A., McPhail, K. (2011). Regulating

for corporate human rights abuses:

the emergence of corporate reporting

on the ILO's human rights standards

within the global garment manufacturing

and retail industry. Critical Perspectives

on Accounting,No. 22, pp. 790-810.

Jentsch, W. M., (2004). Theoritical

approach to industrial relations,

in Kaufman, B. E., (eds), "Theoretical

perspectives on work and the employment

relationship", Cornell University

Press.

Johnstone, R. (2008). 'Harmonising

Occupational Health and Safety Regulation

in Australia: The First Review of

the National OHS Review'.

Kaufman, B. E. (2010). The theoretical

foundation of industrial relations

and its implications for labor economics

and human resource management.Industrial

& Labor Relations Review, 64(1),

74-108.

Marston, A. (2007). Labour monitoring

in Cambodia's Garment Industry: Lesson

for Africa. Realizing Rights - The

Ethical Globalization Initiative.

Marx, K. (1956). Capital. Volume 1,

Chapter 10. Progress Publishers, Moscow,

USSR.

Munck, R.P. (2010) "Globalization

and the labour movement: challenges

and responses," Global Labour

Journal: Vol. 1: Iss. 2, p. 218-232.

Ogunbameru, A. O. (2004). Organisational

Dynamics. Ibadan: Spectrum Books Ltd,

Quinlan, M. (2004). Regulatory responses

to OHS problems posed by direct-hire

temporary workers in Australia. Journal

of Occupational Health and Safety

Australia and New Zealand, Vol. 20(3),

241-254.

Rose, E.D. (2008). Employment Relations.

(3rd ed).London: Pearson Education

Ltd.

Sisson, K., & Marginson, P. (2001).

" Soft Regulation": Travesty

of the Real Thing Or New Dimension?.

ESRC" One Europe or Several?"

Programme, Sussex European Institute,

University of Sussex.

Vogel, D. (2006). The private regulation

of global corporate conduct. Center

for Responsible Business.

|