|

Comparing the Luxury Attitudes of

Young Brazilian and Emirati Females

Luciana

de A. Gil (1)

Ian Michael (2)

Lester W. Johnson (3)

(1) Associate

Professor- Marketing

Universidad Diego Portales, Business

School

Av. Santa Clara 797 (5th floor) Huechuraba

Santiago-Chile

(2) Associate Professor of Marketing

Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab

Emirates

P.O. Box 19282 Dubai, U.A.E

(3) Dr. Lester W. Johnson

Full Professor of Marketing

Faculty of Business & Enterprise

Swinburne University of Technology

Hawthorn VIC 3122, Australia

Correspondence:

Dr. Luciana de A. Gil

Associate Professor- Marketing

Universidad Diego Portales

Business School

Av. Santa Clara 797 (5th floor) Huechuraba

Santiago-Chile

Tel +56-9-68490099

Email: luciana.dearaujogil@gmail.com

Abstract

Luxury brands are affecting women

all around the world and have become

a discernible trend. There is substantial

growth in research focusing on luxury,

which is a reflection of what is seen

in the actual market. However it is

rare to find a study where there is

a comparison between two countries

as different as Brazil and the United

Arab Emirates. Both countries are

becoming well-known for their consumption

of luxury. Brazil is still the leader

in Latin America, and the United Arab

Emirates is attracting an increasing

amount of international investment

related to luxury brands. The aim

of this paper is to investigate and

compare young Emirati females and

Brazilian young females in relation

to their attitudes toward luxury.

We used a questionnaire with measures

already tested in multiple countries.

We find that young Emirati women are

in general more disposed toward luxury

than Brazilian women.

Key words: Young Consumers,

Luxury, Branding, United Arab Emirates,

Brazil

Introduction

Luxury brands are affecting women

all around the world and have become

a discernible trend among women and

men. Moreover, luxury products like

bags, jewelry, shoes, cars, and clothes

are playing a huge role in a woman's

life (Dittmar, Beattie, & Friese,

1995). Market research has predicted

that the younger generation represents

the most important segment that will

influence the global luxury market

over the next decade (Unity Marketing

Inc., 2007). For some people the ownership

of luxury brands is important as a

means of facilitating friendships

with others and achieving popularity

(Ruffin, 2007; Wooten, 2006).

Consumption of luxury brands exists

not only in affluent countries but

also in less developed countries such

as Brazil (Moses, 2000; Troiano, 1997).

The country has the sixth largest

GDP in the world and a population

of around 200 million (L.E.K. Consulting,

2014). From 2000 to 2008 Brazil's

luxury market growth was 35% (Strehlau,

2008). Analysts from Goldman Sachs

even believe that Brazil will become

part of the largest world economies

before 2050 (Keston, 2007). Ever since

the Brazilian economy emerged as a

profitable market for international

companies looking to expand their

businesses, several luxury brands

have taken the opportunity to open

retail outlets and flagship stores

in big cities such as São Paulo

and Rio de Janeiro (Euromonitor, 2014).

Recent studies predicted that by 2030,

the richest Brazilians will increase

from 1% to 5% of the population, and

the middle and upper-middle classes

will increase from 36% to 56% of the

population. Both demographic changes

will drive consumption changes, in

particular an increased interest in

luxury and aspirational goods (L.E.K.

Consulting, 2014). Despite the economic

slowdown in 2013, luxury goods demand

in Brazil remains resilient, with

the area performing above expectations.

The good performance and potential

of the Brazilian market continues

to attract further investment in high-end

products (Euromonitor, 2014). Finally,

the rise of female consumers is changing

the demographic mix of Brazil's shoppers.

More women in the workforce means

households have more discretionary

income. Women have gained increased

financial independence and as a result

have developed unique purchasing tastes.

The health and beauty category, for

instance, is expected to grow by about

12% annually from 2012 to 2017 (L.E.K.

Consulting, 2014).

Consumers in the UAE have become more

fashion oriented and more aware of

luxury brands. The UAE has now been

classified as an emerging economy

and this and a host of other reasons

have consequently increased the attention

and awareness of the locals and non-

locals to the shopping world and shopping

experience (Faisal, Zuhdi, & Turkeya,

2014). The country has several regional

and international luxury brands, which

are keen to attract and sell their

products to the citizens of the UAE,

giving them a well-diversified portfolio,

specifically targeted towards high-end

customers. Although there has been

such a rapid development of the luxury

market, there is scant research on

the marketing of luxury goods and/or

the behaviour of luxury consumers

(Ayoub et al., 2010; Belk, 1995; Dubois,

Laurent, & Czellar, 2001; Gil,

Kwon, Good, & Johnson, 2012; Kapferer,

1998; Phau & Prendergast, 2000;

Prendergast & Wong, 2003; Vigneron

& Johnson, 2004; Wiedmann, Hennigs,

& Siebels, 2007) with particular

reference to the UAE. The UAE has

been listed among the best places

worldwide for organizations to conduct

business, and there are over 400 multinational

brands present in Dubai alone (Balakrishnan,

2008). The country has become famous

for being an exquisite destination

for anyone who aspires to live in

the luxury circuit. Statistics by

UAE's Ministry of Economy showed that

within the last decade, the country

has more than doubled its GDP (IMF,

2009) and the economy has continued

to see a positive trend in its economic

growth rate, even with the recent

global recession (Vel, Captain, Al-Abbas,

& Hashemi, 2011).

The purpose of this research paper

is to examine the various factors

that influence UAE and Brazilian young

female citizens in relation to their

attitudes towards luxury brands. This

research looks into the unique social

influences affecting their perceptions

of luxury products, as well as focuses

on consumer behavior and the underlying

motives that encourage UAE and Brazilian

young female citizens to purchase

luxury products.

Background about

luxury

Luxury brands are those whose price

and quality ratios are the highest

in the market (Wiedmann, Hennigs,

& Siebels, 2009), and those that

range in luxurious services like elite

hotels and first class airline tickets,

and luxurious products like jewelry,

cars, furniture, clothes, shoes, bags

and much more. "Luxury is the

domain of culture and taste"

(Kapferer & Bastien, 2009, p.

318).

Luxury is very interesting; it is

both simple and complicated at the

same time. To simplify the complications

of luxury, a timeline of its history

will be previewed. "Luxury was

the visible result of hereditary social

stratification (kings, priests and

the nobility, versus the gentry and

commoners)" (Kapferer & Bastien,

2009, p.313). The rich, then and now,

tend to communicate their social advantage

by buying and displaying their luxury

goods. This was classified as "old

luxury", which was also defined

by "snobbish, class oriented

exclusivity-goods and services that

only a small segment of the population

can afford or is willing to purchase"

(Granot & Brashear, 2008, p. 991).

However, in the eighteenth century,

globalization has turned the table

around; it created a materialistic

and fluid society in which hierarchy

and transcendent social stratification

are destroyed. In other words, a democratic

world or a classless society was created

in which each one can have an even

chance of succeeding through work.

This is also called "new luxury"

and "Populence-popular opulence",

which "includes products for

mass-market appeal to consumers across

various income and social classes"

(Granot & Brashear, 2008, p. 991).

On the other hand, social stratification

has not completely disappeared; human

nature urges us to know where in society

a person stands. Therefore, here comes

the role of luxury in creating a democratic

social hierarchy where a luxury brand

is placed in a position of superiority

with respect to its client (Kapferer

& Bastien, 2009).

Luxury in definition varies a lot,

and there is some confusion nowadays

on what really makes a luxury product,

brand, and company. As stated earlier,

"Luxury brands are those whose

price and quality ratios are the highest

in the market" (Wiedmann et al.,

2009, p. 2). It is further explained

by Kapferer and Bastien (2009) that

luxury is the expression of a taste,

of a creative identity, of the intrinsic

passion of a creator; luxury makes

a bold statement, 'this is what I

am', not 'that it depends'. The authors

further reiterate that a luxury brand

should tell a story of its own, whether

is it real and historic, or invented

from scratch. Moreover, "luxury

is a key factor in differentiating

a brand in a product category, as

well as a central driver of consumer

preference and usage" (Wiedmann

et al., 2009, p. 1).

According to Husic and Cicic (2009),

luxury goods are goods for which the

simple use or display of a particular

branded product gives prestige to

the owner, apart from any other functional

utility and (Phau & Prendergast,

2000, p. 123) luxury brands are those

that "evoke exclusivity, they

have a well-known brand identity,

enjoy high brand awareness and perceived

quality, and retain sales levels and

customer loyalty". Phau, Teah,

and Lee (2009) have identified luxury

brands as those where ratio of functionality

to price are low, while the ratio

of intangible and situational utility

to price is high. Based on these definitions,

luxury items are high priced products

with good quality that allow people

to acknowledge their status and wealth

to others. Other characteristics that

classify luxury items with higher

prices and exclusivity include the

packaging, store locations, advertising

methods and most importantly, the

elite brand name (Husic & Cicic,

2009).

"Luxury goods buyers are typically

looking for outstanding quality and

image in the brands they favor, and

are willing to pay the high price

which signals the good's exclusivity"

(Türk, Scholz, & Berresheim,

2012, p. 88). A dilemma exists as

some believe that if a luxury brand

gets over-diffused, it could lose

its image and 'luxury' characteristics

(Giacalone, 2006). One of the allures

of luxury brands is exclusivity.

Research question

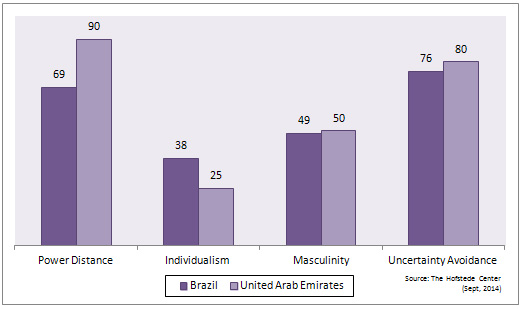

We used the four dimensional tool

developed by Hofstede (1984) to compare

these two nations. According to this

author the differences among cultures

can be understood by accounting for:

individualism, power distance, uncertainty

avoidance and masculinity. Considering

the first of these four dimensions,

both Brazil and the United Arab Emirates

have a high level of acceptance of

Power Distance, however the score

is much higher for the Arab country.

Power distance reflects the fact that

both societies respect hierarchy and

find it acceptable that more important

people have benefits. Nonetheless,

in the South American nation its score

is marked by a respect for elders

and the powerful bosses of industry

and the fact that people there are

seen as equals. In the Emirates there

is an inherent difference between

the powerful and the rest, a natural

hierarchy not to be second-guessed.

Also, neither country is individualistic,

but Brazil, with a score of 38 for

individualism, is much less collective

than the United Arab Emirates, with

a score of 25. The countries' scores

in Masculinity are almost the same,

49 for Brazil and 50 for UAE, so both

countries have an equal consideration

for values such as competition, success,

caring for others and quality of life.

Finally, both countries show high

scores for uncertainty avoidance,

which means people from these nations

prefer strong institutions and rules

that cast away most of the ambiguity

of the present and the future (The

Hofstede Centre, 2014). Scores can

be viewed in Chart 1.

Chart 1: Scores for Brazil and

Emirates Cultural Values - The Hofstede

Centre

There has been substantial growth

in designer clothing in the UAE as

of the year 2013 due to the increase

in tourists who come to Dubai on luxury

shopping trips (Sophia, 2013). Emirati

students are influenced by the globalization

of the country and the many changes

that have occurred in the UAE economy

and culture. The UAE is attracting

numerous luxury companies to establish

their offices in the country. The

country is fast becoming one of the

major global hubs for luxury goods

and services. People in the UAE are

more aware of luxury brands and more

interested and keen on obtaining them.

The UAE's economy has emerged strongly

in the last three to four years, which

consequently increased the attention

and the awareness of Emirati locals

to the shopping world and shopping

experience (The Hofstede Centre, 2014).

Salama (2008) states that UAE consumers

rank as some of the world's biggest

consumers of luxury brands. Moreover,

Emirati local shoppers are the world's

second biggest buyers of brands such

as Gucci, which is at 31 percent,

Chanel at 21 percent, while Giorgio

Armani ranks the third at 19 percent.

According to The Nielsen Company (2008),

three in five UAE consumers said people

wear designer brands to project social

status. The survey also revealed untapped

potential for luxury fashion brands

in the UAE to expand their apparel

businesses into other products such

as mobile phones, laptops, flat-screen

televisions, MP3 players and kitchen

appliances. Besides, the survey found

that 57 percent of shoppers would

buy luxury branded mobile phones,

compared with a global average of

34 percent, and 46 percent would buy

fashion branded laptops, compared

with a global average of 29 percent.

Our research question is: Do Emirati

women have a more positive attitude

toward luxury than Brazilian women?

Methodology

In Brazil our study used a self-report,

paper and pencil survey instrument

to collect data from university students

in São Paulo state, Brazil,

with approval from the university

and students. The total sample consisted

of 165 students; the majority between

the ages of 18 and 24. For the purpose

of this study we deleted the males

from the sample given that our purpose

here is to compare female university

students in Brazil with female university

students in United Arab Emirates.

For that reason we used 76 Brazilian

female respondents from our sample.

To be able to examine the attitudes

of Emirati female students toward

luxury items, we used the same survey

instrument, but with an online approach

using Surveymonkey. The survey was

distributed to 175 female students

from various universities in the UAE,

their age ranging, from 18 to 25 years

old (or more).

Measures

For the purpose of this investigation

we use two different settings of attitude

toward luxury scale. Both of them

were tested in multiple countries

and we believe that by using two different

author's scales we improved our chances

of embracing differences in cultures

and improving our conclusions as a

result of this study

Attitude toward luxury concept:

Attitudes represent a consumer's overall

evaluations of an object such as a

product/brand or store; it is a response

involving general feelings of liking

or favorability (American Marketing

Association, 2007). We use a short

version of the attitude toward luxury

scale created by Dubois and Laurent

(1994) that fits the scope of our

research.

The Dubois and Laurent (1994) scale

is the most well known scale for attitudes

toward luxury and has been used in

several studies such as Tidwell and

Dubois (1996), Dubois, Czellar and

Laurent (2005), Dubois, Laurent and

Czellar (2001) and, Kim, Baik and

Kwon (2002). According to Czellar

(2007) who used this scale on her

study in 2005, no Cronbach's alpha

was reported because her particular

study did not use a conventional domain

sampling paradigm (Churchill, 1979),

but focused more on content validity

as advocated by Rossiter (2005). From

this perspective, she justified that

alpha coefficients are less informative

than from the perspective of domain

sampling. Sample of the items are

"In general, luxury products

are better quality products",

"Luxury products make life more

beautiful" anchored by "disagree-

agree".

Attitude toward luxury brands:

This scale is an adaptation

of the scale created by Mitchell and

Olson (1981) and it was used by Rios,

Martínez, Moreno, and Soriano

(2006). It is measured by the mean

of four seven-point evaluative scales

(good-bad, dislike very much-like

very much, pleasant-unpleasant, poor

quality-high quality). The original

reported Cronbach's alpha was 0.88.

Sample of the items are "What

degrees do you like or dislike luxury

brands?" anchored by "dislike

very much - like very much" and

"In my opinion luxury brands

are" anchored by "good -

bad."

Findings

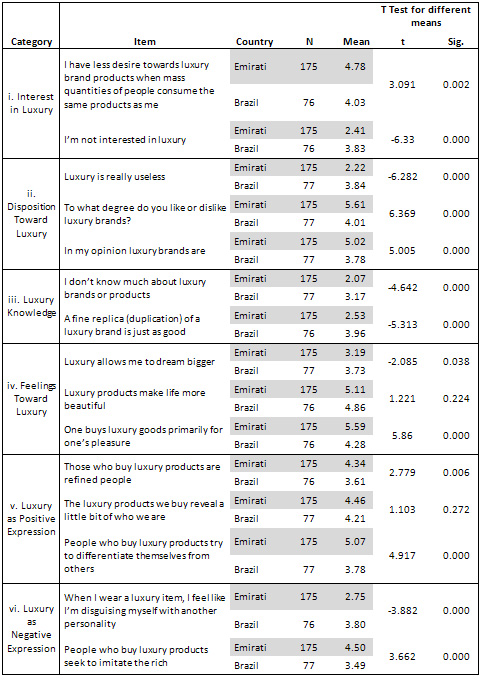

A first analysis reveals that young

Emirati women are better disposed

toward luxury than Brazilian young

women; this comparison can be viewed

in Table 1. We divided 15 questions

into six categories to compare more

comprehensibly these groups. These

categories were made by the co-authors

based only on semantic similarities.

Interest in Luxury: Two

items evaluate this aspect: 'I'm not

interested in luxury' and 'I have

less desire towards luxury brand products

when mass quantities of people consume

the same products as me'. The Emirati

women show more interest in luxury

by this measure. Their responses are

statistically different from those

of Brazilian women on both items;

they express more interest in luxury

and more interest in it being exclusive.

To the first question Emirati achieved

the lowest average, 2.4 against Brazil's

3.8, that is to say they do not agree

to 'I'm not interested in luxury',

while Brazilian women express indifference.

Disposition toward Luxury: This

category considers three items: 'Luxury

is really useless', 'To what degree

do you like or dislike luxury brands?

(dislike - like) and 'In my opinion

luxury brands are…' (bad - good).

Again Emirati hold the stronger disposition

toward luxury, with better results

for all the items. While Brazilians

are indifferent to the expression

that luxury could be useless (3.8),

Emirati respondents showed disagreement

with the phrase (2.2). Furthermore,

Emirati women like luxury (5.6) and

think luxury brands to be good (5.0),

while Brazilians are indifferent to

both considerations (4.0 and 3.8 respectively).

Luxury Knowledge: Luxury knowledge

contains two items: 'I don't know

much about luxury brands or products'

and 'A fine replica (duplication)

of a luxury brand is just as good'.

The conclusion from this category

is straightforward. Emirati female

university students think they know

more about luxury than do Brazilian

female university students. For both

items the means are statistically

different, and while Emirati respondents

disagreed in both cases, Brazilian

disagreed only in the first item.

Emirati's average was (2.1) for the

first item and (2.5) in the second,

showing strong disagreement, while

Brazilians answered the first item

with a mean of (3.2), that shows a

lesser disagreement, and were indifferent

as to the second statement, with a

mean of (4.0).

Feelings toward Luxury:

This group is comprised of three items:

'Luxury makes me dream', 'Luxury products

make life more beautiful' and 'One

buys luxury goods primarily for one's

pleasure'. This class is not as clear

as the three before it; still it seems

as if Emirati women think more of

luxury than Brazilians do. Emirati's

think luxury products make life more

beautiful (5.1) and are bought for

personal pleasure (5.6), but do not

agree with the allegation that it

makes them dream (3.2). Meanwhile,

Brazilians think life is more beautiful

with luxury as well (4.8), but are

indifferent to the other two remarks.

Luxury as Positive Expression:

This groups contains three items:

'Those who buy luxury products are

refined people', 'The luxury products

we buy reveal a little bit of who

we are' and 'People who buy luxury

products try to differentiate themselves

from others'. Answers for these items,

regardless of the origin of the respondents,

show neither agreement nor disagreement

with the postulate. Only for the last

of them, intent of differentiation,

do Emirati women agree (5.1), while

Brazilians remain indifferent (3.8).

The answers also diverge mildly from

the midpoint in the case of the first

item and, while Brazilians moderately

disagree (3.6), Emirati respondents

are rather indifferent but tending

to the opposite opinion (4.3).

Luxury as Negative Expression: The

last two items make this last category:

'When I wear a luxury item, I feel

like I'm disguising myself with another

personality' and 'People who buy luxury

products seek to imitate the rich'.

This is a group of apparent contradiction.

Emirati respondents completely disagree

with the first item (2.7) while maintaining

a very mild agreement with the latter

(4.5). Brazilians however think nothing

of the feeling of disguising (3.8)

and at the same time consider luxury

a way to imitate the rich (3.5), though

conservatively. Nevertheless, means

are statistically different in both

cases, suggesting the mean is lower

for Emirati for the first item, and

higher for the second one.

This analysis shows unmistakably that

Emirati female university students

hold a better opinion and relationship

with luxury than those of Brazil origin,

as noted on Table 1. Nonetheless,

this data is comprised almost exclusively

by women between the ages of 18 and

25, and it is also interesting to

test if age has something to do with

their relationship with luxury. While

younger women could be more easily

pushed into craving for luxury products,

older ones could be resetting their

preferences to favor more expensive

and exclusive products as well. Therefore,

we divided our data into four groups,

Brazilian and Emirati women of 21

or fewer years of age, and Brazilian

and Emirati women of 22 or more years

of age. The comparison between these

age groups can be found on Tables

2, for Brazilian females, and 3, for

Emiratis.

Table 1. Means for each item -

Emirati versus Brazilian females

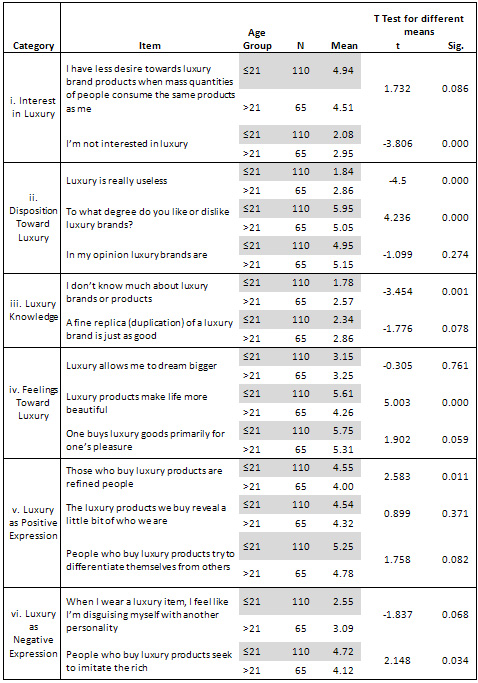

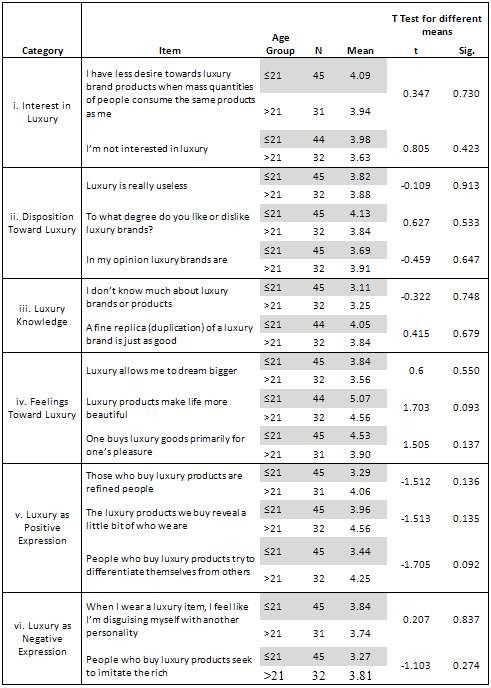

We believed we could make some deeper

analysis by separating females older

and younger than 21 years old. Below

there are our findings for Emirati

and Brazilian women.

Interest in Luxury - Emirati:

younger women, as expected, show higher

interest in luxury (2.1 against 3.0)

and also greater concern on exclusiveness

(4.9 against 4.5). Brazilian: incredibly,

younger women's mean for no interest

in luxury is higher than that of the

older Brazilians (4.0 against 3.6),

however, this difference is not statistically

significant. Neither is the difference

between younger and older women for

the exclusiveness item (4.1 and 3.9

respectively), so luxury interest

does not seem to change in Brazil

with age.

Disposition toward Luxury-

Emirati: again, younger women

like luxury brands the most (5.9 against

5.0) and express a greater disagreement

with it being useless (1.8 against

2.9).

Surprisingly, there is no statistically

significant difference in how they

see luxury brands, good or bad; both

age groups consider them to be good.

Summing up, younger female university

students from the Emirates show a

better disposition toward luxury brands

and products than the elder.

Brazilian: in this country

no mean is statistically different

when separated by age group.

Nevertheless, older women have a worse

image of luxury's usability and whether

or not they are good, but somehow

they dislike them less than the younger

women.

Luxury Knowledge-

Emirati: both means reflect

that young women are more knowledgeable

than the elder ones, yet only one

of them is statistically different

across age groups. Younger women say

they know more about luxury than elder

women do (1.8 versus 2.6).

Brazilian: for the third

time Brazilian respondents confirm

they do not change with age, both

answers cannot be said to be statistically

different. Furthermore, the means

change little, for knowledge they

are 3.1 for younger and 3.3 for elder

and for exclusiveness 4.0 and 3.8

respectively.

Feelings toward Luxury-

Emirati: this categorization

shows an important difference in the

beauty luxury contributes to life,

younger women obtaining a mean of

5.6 against the rather indifferent

4.3 obtained by older respondents.

The difference is not statistically

significant on both other items, even

though for the item of buying luxury

for one's own pleasure it is not a

small difference, the higher mean

obtained by the younger women again

(5.8 versus 5.3). All in all it appears

younger girls have the edge in this

category too.

Brazilian: there is

no statistically significant difference

in this tier either. Regardless, the

scores are higher for younger Brazilian

women in all three cases. Younger

women's mean of 5.1 compares positively

against the 4.6 of their older peers

in beauty added to their life; the

results are 4.5 against 3.9 in considering

luxury as being primarily for private

pleasure and finally 3.8 versus 3.6

in luxury being dream inducing.

Luxury as a Positive Expression-

Emirati: younger and older

women believe luxury is differentiating,

but there is no statistically valid

difference between them at 5% confidence.

Both age groups are in mild agreement

with the idea that the luxury consumed

reveals something about the buyer,

with means of 4.5 for the younger

and 4.3 for the older women; but no

statistical difference between them.

Finally, an expected result, younger

women think luxury is more for refined

people than older women do (4.5 and

4.0 respectively), still, none of

them believes this too strongly. Overall

this category does not show strong

change with age, maybe even no change

at all in general feelings.

Brazilian: Brazilians

show no statistically significant

difference once again. What is more

interesting is that the scores are

actually higher for the older group

for this category. Furthermore, at

the 10% level we could say that younger

respondents disagree with the statement

that luxury serves as a way of differentiating

oneself more than older Brazilians

do. Even though slightly, it looks

as if older women see luxury as a

way to express themselves a little

more.

Luxury as a Negative Expression-

Emirati: younger respondents

see luxury as a way to imitate the

rich (4.7), while older ones do not

agree, nor disagree, with that statement

(4.1). Neither feels like in disguise

when using luxury products, yet at

the 10% level younger women disagree

a little more with the statement (2.5

versus 3.1). Emirati female university

students do not see luxury as a negative

expression, but age seems to make

their responses a little more moderate.

Brazilian: no statistically

significant difference in this category,

even at the 10% level. Means for feeling

of disguising are almost the same;

3.8 the younger group and 3.7 the

older one, and what is more, both

showing indifference to the question.

Younger respondents do seem to show

a little more disagreement with the

idea that luxury serves as a way to

imitate the rich (3.3 against 3.8)

but again, there is no statistically

significant difference.

Table 2: Means for each item -

Emirati females, younger (<21)

versus older (>21)

Table 3: Means for each item -

Brazilian females, younger (<21)

versus older (>21)

Conclusions

and further research

Overall, it appears as if age

does not influence attitudes toward

luxury the same way for Emirati and

Brazilian young females. While Emirati

female university students present

a tendency toward more conservative

answers when growing older, Brazilians

do not change their view with age.

Although, when comparing both countries;

Emirati respondents are better predisposed

toward luxury products and brands

at any age. This may be because they

see more of them (luxury products)

than the Brazilians or maybe because

their culture welcomes luxury more.

Regardless, this does not explain

the difference in the evolution of

this disposition. Possibly Brazilians

have relatively low exposure to luxury

when compared with Emirati, which

could be the reason they change so

little with age, or maybe there is

something cultural that makes their

opinions mature earlier than those

of Emirati women; either way it has

important marketing implications.

The above hypothetical statements

can be used for future research projects.

The perceptions that luxury may serve

as a negative expression should not

be incentivized by luxury companies,

which should emphasize luxury as positive

expression of one's personality. Consequently,

negative perceptions should not be

encouraged, while those for positive

expression need to be spurred. It

is a bad signal that young women consider

those who consume luxury products

to be disguising themselves, or trying

to pass as something they are not.

Indifference is not good either if

one is trying to promote luxury, consumers

should see luxury as a positive way

of expression. These findings from

our research should therefore be very

helpful to luxury brand manufacturers.

The luxury market

used to be all about cars, watches,

and home furnishings. Nowadays, luxury

is about the experience. Consumers

will buy the product if the experience

exceeds their expectations. It used

to be all about materials; but the

new luxury is all about the experience.

There is even a new phenomenon called

"Luxflation", and according

to an article by Goff (2007) published

in the Washington Times, the concept

of "Luxflation" is what

the majority of consumers are looking

for when it comes to the purchase

of luxury products and services. When

it comes to products shoppers prefer

products that are unique and better

in quality, it is human nature to

seek the best. For example, Goff (2007)

mentioned that products used to be

very standard like a cup of coffee,

an ice cream or a chocolate but now

when one purchases these type of products

one can customize it by adding sugar,

flavors or cream, in fact some establishments

offers a great variety of different

ingredients to choose from and change

enabling the consumer to customize

it. That's what drives consumers to

purchase products, products that are

different. Our research did not look

into the phenomena of customization

and mass-customization in luxury purchase.

This angle would be a very interesting

topic for future studies.

Furthermore, Emirates is a 'World

bank designated high income country'

and Brazil 'World bank designated

Upper Middle Income' with pockets

of extreme poverty and in a continent

with extreme poverty. Disposable income

and 'national prejudice' (e.g. the

stigma of being seen to wear luxury

items among the poor and underprivileged

who cannot afford basic items), surely

plays a part (World Bank, 2015). There

is also a trend against those who

purchase 'luxury items' as being easily

deceived and victims of mass marketing.

It really depends on what social demographic

you speak with and the level of education

of the individual; both issues should

be more investigated in the future.

Future research could also include

other demographic groups e.g. including

the male gender and doing a cross

comparison for example between Emirati

male consumer and Brazilian male consumer,

and further comparing all four demographic

groups. Further in later research

other age groups can be investigated

for example between consumers of the

two nations. More measures should

be included in order to have a more

complete view of what is happening

in each country. Finally the study

could become global and encompass

more than 6-8 nations.

References

American Marketing Association. (2007).

Dictionary of Marketing Terms. Retrieved

Oct, 5, 2007, from http://www.marketingpower.com/_layouts/Dictionary.aspx

Ayoub, A., Abdulla, A., Anwahi, A.,

Khoory, R., Michael, I., & Gil,

L. A. (2010). An investigation on

the attitudes toward luxury among

female Emirati students. Paper presented

at the Proceedings of the Academy

of International Business Middle East

and North Africa, Dubai, U.A. E.

Balakrishnan, M. S. (2008). Dubai-a

star in the east: a case study in

strategic destination branding. Journal

of Place Management and Development,

1(1), 62-91.

Belk, R. W. (1995). Collecting as

Luxury Consumption: Effects on Individuals

and Households. Journal of Economic

Psychology, 16(3), 477-490.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A Paradigm

for Developing Better Measures of

Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing

Research, 16(1), 64-73.

Czellar, S. (2007, June, 30). [Personal

communication].

Dittmar, H., Beattie, J., & Friese,

S. (1995). Gender identity and material

symbols: Objects and decision considerations

in impulse purchases. Journal of Economic

Psychology, 16(3), 491-511.

Dubois, B., Czellar, S., & Laurent,

G. (2005). Consumer segments based

on attitudes toward luxury: Empirical

evidence from twenty countries. Marketing

Letters, 16(2), 115-128.

Dubois, B., & Laurent, G. (1994).

Attitudes towards the concept of luxury:

An exploratory analysis. In J. A.

Cote & S. M. Leong (Eds.), Asia

Pacific Advances in Consumer Research

(Vol. 1, pp. 273-278). Provo, UT:

Association for Consumer Research.

Dubois, B., Laurent, G., & Czellar,

S. (2001). Consumer rapport to luxury:

Analyzing complex and ambivalent attitudes

(pp. 1-56). Jouy-en-Josas, France:

Consumer Research Working Paper n°736.

Euromonitor. (2014). Luxury goods

in Brazil. http://www.euromonitor.com/luxury-goods-in-brazil/report.

Faisal, M., Zuhdi, M., & Turkeya,

S. A. B. (2014). A study on the perceptions

and attitudes of luxury among female

Emirati students. Zayed University.

Giacalone, j. A. (2006). The market

for luxury goods: the case of the

Comité Colbert. Southern Business

Review, 32(1), 33-40.

Gil, L. A., Kwon, K.-N., Good, L.

K., & Johnson, L. W. (2012). Impact

of self on attitudes toward luxury

brands among teens. Journal of Business

Research, 65(10), 1425-1433.

Goff, K. G. (2007, September 30).

´Luxflation´ for all:

costly small indulgences, mass-market

luxury brands. Washington Times. Retrieved

from http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2007/sep/30/luxflation-for-all/?page=all

Granot, E., & Brashear, T. (2008).

From luxury to populence: inconspicuous

consumption as described by female

consumers. Psychology, 14(1&2),

41-51.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture's consequences:

international differences in work-related

values. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Husic, M., & Cicic, M. (2009).

Luxury consumption factors. Jounal

of Fashion Marketing and Management,

13(2), 231-245.

IMF. (2009). World Economic Outlook.

http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

Kapferer, J.-N. (1998). Why are we

seduced by luxury brands? Journal

of Brand Management, 6(1), 44-49.

Kapferer, J.-N., & Bastien, V.

(2009). The specificity of luxury

management: turning marketing upside

down. Journal of Brand Management,

16(5), 311-322.

Keston, J. (2007). Another BRIC in

economic wall - The arrival of developing

countries. Retrieved Jan, 21, 2008,

from http://localtechwire.com/business/local_tech_wire/opinion/story/1867292/

Kim, J., Baik, M., & Kwon, J.

(2002). A comparison of Korean, Japanese

and Chinese consumers' perceptions

of the luxury product. International

Journal of Digital Management, 2.

L.E.K. Consulting. (2014). Spotlight

on Brazil: understanding the Brazilian

consumer. http://www.lek.com/sites/default/files/0114_LEK_BrazilSpotlight_final%28v3%29.pdf:

L.E.K. Consulting.

Mitchell, A. A., & Olson, J. C.

(1981). Are product attribute beliefs

the only mediator of advertising effects

on brand attitudes? Journal of Marketing

Research, 18, 318-332.

Moses, E. (2000). The $ 100 billion

allowance- accessing the global teen

market. New York: John Wiley &

Sons Inc.

Phau, I., & Prendergast, G. (2000).

Consuming luxury brands: The relevance

of the "rarity principle".

Journal of Brand Management, 8(2),

122-138.

Phau, I., Teah, M., & Lee, A.

(2009). Targeting buyers of counterfeits

of luxury brands: a study on attitudes

of Singaporean consumers. Journal

of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis

for Marketing, 17(1), 3-15.

Prendergast, G., & Wong, C. (2003).

Parental influence on the purchase

of luxury brands of infant apparel:

an exploratory study in Hong Kong.

Journal of Consumer Marketing, 20(2/3),

157-169.

Rios, F., Martínez, T., Moreno,

F., & Soriano, P. (2006). Improving

attitudes toward brands with environmental

associations: an experimental approach.

Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(1),

26-33.

Rossiter, J. (2005). Reminder: a horse

is a horse. International Journal

of Research in Marketing, 22(1), 23-25.

Ruffin, J. (2007). Luxuries are things

you wouldn't buy if no one saw you

use them. Retrieved Sept, 14, 2007,

from http://www.newsobserver.com/690/story/539390.html

Salama, V. (2008, October 20). UAE

loves luxury. The National. Retrieved

from http://www.thenational.ae/business/retail/uae-loves-luxury

Sophia, M. (2013, December 16). UAE

ranked world's 11th biggest clothing

importer. Gulf Business.

Strehlau, S. (2008). Marketing do

luxo (1 ed. Vol. 1). São Paulo/SP:

Cengage Learning.

The Hofstede Centre. (2014). Country

comparison. Retrieved September 9th,

2014 http://geert-hofstede.com/arab-emirates.html

The Nielsen Company. (2008). Nielsen

global luxury brands survey.

Tidwell, P., & Dubois, B. (1996).

A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Attitudes

Toward the Luxury Concept in Australia

and France. In R. Belk & R. Groves

(Eds.), Asia Pacific Advances in Consumer

Research (Vol. 2, pp. 31-35). Provo,

UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Troiano, J. (1997). Brazilian teenagers

go global - Sharing values and brands.

Marketing and Research Today, 25(3),

149.

Türk, B., Scholz, M., & Berresheim,

P. (2012). Measuring service quality

in online luxury goods retailing.

Journal of Electronic Commerce Research,

13(1).

Unity Marketing Inc. (2007, Apr, 1).

Generations of luxury: What 'Young

Affluents' want and what it means

to luxury marketers. from http://www.marketresearch.com/map/prod/1489810.html

Vel, K. P., Captain, A., Al-Abbas,

R., & Hashemi, B. A. (2011). Luxury

buying in the United Arab Emirates.

Journal of Business and Behavioural

Sciences, 23(3), 145-160.

Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W.

(2004). Measuring perceptions of brand

luxury. Journal of Brand Management,

11(6), 484-506.

Wiedmann, K.-P., Hennigs, N., &

Siebels, A. (2007). Measuring consumers'

luxury value perception: A cross-cultural

framework. Academy of Marketing Science

Review, 7, 1-21.

Wiedmann, K.-P., Hennigs, N., &

Siebels, A. (2009). Value-based segmentation

of luxury consumption behavior. Psychology

and Marketing, 26(7), 625-651.

Wooten, D. B. (2006). From labeling

possessions to possessing labels:

Ridicule and socialization among adolescents.

Journal of Consumer Research, 33(2),

188-198.

|